In late 2015, I had a recurrence of my bowel cancer, in the form of a couple of liver metastases. So, it was agreed that a liver resection for my recurrence was definitely the way to go. The scans were done, the tumours were operable, so the date was set: 5th December. If all went to plan, I’d be in and out in time for my daughter’s birthday on the 11th.

Ah, plans…! No matter how well laid, they are so prone to going awry. Regardless of the gender or species involved.

In my case, the emotional distress of the recurrence had led to what it always does: stress eating.

Ironically, as I sit here typing this, I’m back up to 20 stone (280 lb, 127 kg) due to all the stress eating associated with the wait for the results I got yesterday. This, on top of the weight I’ve gained from the ongoing stress related to the three sets of surgeries I’ve had this year. Happily, the scans have not revealed any new recurrences, so I get the next three months off. As it stands, I’m currently, and once again, cancer free. Yay! ![]()

But, but in December 2015, I was neither cancer free nor anywhere near as light as I’d want to be to face a surgery. My journal entry on October 20th recorded my weight as 19 stone 4 pounds (270 lb, 122 kg) on October 20th. What with all the stress and uncertainty in the six weeks between that time and my surgery, it seems very unlikely I would have been any lighter when I went under the knife.

According to the liver surgeon, being fat doesn’t actually impact that much on the surgery. However, the fitter and lighter you are, the easier the recovery. I’d always recovered well from surgeries, so this didn’t overly concern me. Not that it mattered; I was the weight I was and it was too late to do anything about it.

And so, on the 5th December 2015, I went to Bristol to have a liver resection for my recurrence. I’d been warned that, while it was hoped to do the surgery with laparoscopy, they wouldn’t know the extent of the situation until they got in there. So they might have to go to open surgery…

By Samuel Bendet, US Air Force

The liver surgeon managed not to go to open surgery, which meant less scarring. However, in order to achieve this, the surgery took five and a half hours.

Part of the reason the surgery took so long was the need to fight through all the gloop left over from the original surgery. That gloop was what was left from the ‘collections’ around the original surgical site. The same collections that had caused the delay of my bowel surgery and, ultimately, my colostomy bag. Also the collections that kept appearing on my scans, resulting in the laparoscopic investigation I mentioned a couple of posts ago.

These ‘collections’ had been making my life difficult for more than a year, at this stage, but the liver resection for my recurrence would see the end of them. Not that they didn’t go down without a fight…

Part of the reason that the liver surgeon struggled for so long, instead of simply opening me up, was to limit the damage and scarring to my body. In essence, the body can only take so much damage before surgery becomes too difficult. Largely because of things like collections and the gloop they become.

This gloopy mess effectively glues the internal organs together. Getting through this glue is both time consuming and potentially dangerous. Sometimes it might need to be cut. These cuts can effectively be blind, due to the presence of the glue, meaning there is a real risk of bleeds. Just trying to tease the organs apart might lead to tearing and bleeding. Even if none of this happens, the increase in time means longer under general anaesthetic, which carries it’s own risks.

The upshot it that there is a finite number of surgeries that any given patient can receive. There is a finite amount of damage that can be worked around. Open surgeries cause more damage than laparoscopic surgeries, which is why the team worked so hard to keep it keyhole.

Because the surgical team was awesome. And I was lucky to have them.

When it came to what they’d found during the liver resection for my recurrence, however, I was not so lucky. Despite the fact the scans showed only two metastases, there were three distinct tumours, and another on the way. That said, three of these areas were very close together. As such, one possibility was that they merged into one on the scans, leading to the confusion. Another, far more worrying, possibility was that the extra tumours had grown in the time between the scans and the surgery. Which would have been very fast indeed.

But there would be plenty of time to have sleepless nights about that, later; for now it was about my recovery.

And that didn’t start well. I spent the rest of Saturday and all of Sunday in the recovery area. I was so disorientated and confused that I didn’t even notice that there were other patients in there with me until Sunday.

By Monday I was sufficiently improved to be moved up to a room. At which point the assorted tubes were removed, including the drain, and there was talk about me going home on Wednesday 9th. Which was perfect: back in time for the birthday. The drain had been left in longer this time, to make sure there was no repeat of the ‘collections’ issue.

By Tuesday, I was up and around a bit; being taken for walks by the Physio – up and down stairs, and everything.

On Wednesday, I felt rotten. I didn’t want to get out of bed and I had no energy. The reason quickly became obvious; I’d spiked a fever. I had pneumonia!

Remember earlier when I mentioned that being fat could impact on a patient’s ability to recover easily? Yeah, well those particular chickens had come home to roost. Hard! The thing about laparoscopy is that the abdomen in inflated during the process to create the space for the surgery.

The lungs are all squished on the far side of the diaphragm.

Creating this space in the abdomen, necessarily restricts the available space in the lungs. And I was like that for five and a half hours. I then spent most of the following 48 hours in a reclined sitting position, in the recovery area, which further cramped my lungs. In these circumstances, pneumonia was pretty much inevitable.

The liver surgeon certainly saw it coming. At the first sign of fever, the IV antibiotics went in. I never even had time to cough! Which isn’t to say that I wasn’t impacted in other ways.

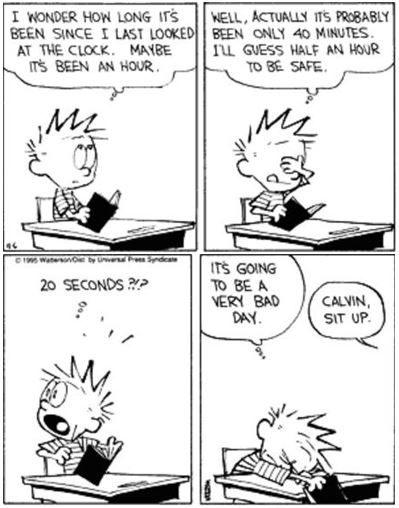

My concept of time was shattered. I’d rest and try and get some sleep. I’d doze off and wake up hours later, to find that minutes, sometimes only seconds, had passed. It reminded me of cartoons and comic strips of how children feel in school.

I knew I was struggling but I thought I was coherent. I really can’t have been because Julie sent me the following text on the Wednesday evening:

“Need you to get your head straight so you can come home. I think I’ll come up earlier tomorrow to try to catch [the liver surgeon] to see what the plan is.“

Seeing that she was worried, I wanted to reassure her. I knew I wasn’t quite right, so I spent ages putting together a reply that made sense. I proof-read it thoroughly and, finally, sent it off; happy that I’d got it right. Julie showed me what I’d written the following day, it was this:

“I’ve mins scared from you.

They seem to be sellting people down around. I suspect the naughty people the ones you grassed will be first the be

screwed over.

I also have be used what the rules are but that remembering them tomorrow would be a mistake!“

Strangely, that didn’t reassure her in the slightest!

The interesting thing about delirium, it seems, is that even if you know it’s got you; you can’t tell that you’re in trouble. I dread to think what I might have said to the nurses during that night.

By the following day, my mind was closer to where it should be, which meant my pneumonia was under control. So, they decided to deal with something else that clearly wasn’t: my constipation.

Having spent so long in surgery and then so much longer on some really powerful pain killers, my bowels had, basically, shut up shop. So I was given IV laxatives. These forced my bowels to reconsider their, previously, hard line position both very quickly, and very thoroughly. And, quite often as well…

And, from that point on, I spent the next 48 hours slowly getting better. I was still on IV antibiotics, but I was able to work with the physio again. So, on Saturday 12th, I was allowed to go home. Having spent the previous day, my daughter’s birthday, stuck in hospital.

I was extremely disappointed about missing the birthday. Being ill is one thing, but when it messes with the people I love, that’s another thing entirely. My daughter, of course, was very good about it. But it’s times like this that I really hate my cancer.

But, anyway; home, sweet home.

For all of four days.

On the Tuesday night, I’d started feeling some discomfort in my lungs. We decided that if it hadn’t cleared up by the following morning, I’d do something about it. It hadn’t, so I called the after-care service at the hospital. After some umming and ahing, I got a call from the liver surgeon. We had a chat, and he said I should head into the local A&E.

So I packed a bag (because I’d learned by this stage) and presented myself at A&E. They promptly admitted me and packed me off to the AMU for the night. The Acute Medical Unit is for people who are in trouble, but not an emergency. This was definitely me, because they put me back on IV antibiotics, gave me a window bed and left me to my own devices… My phone and my Kindle. You see what I did there?! Devices! It’s a homonym pun…

I’ll get my jacket…

Anyway. It turned out to be a Pleural Effusion, brought on by the pneumonia. Nothing particularly serious, in my case, just something that needed antibiotics, and time. So they moved me to the long stay ward that specialised in abdominal issues. I initially ended up in bed A3, which was a window bed, and suited me fine. The wards were very hot and the windows could be opened, which made lying on the rubber beds just about bearable.

It turned out that the ‘A’ bay that I was in was reserved for the patients needing the most care. Which wasn’t me, because I was completely mobile and dealing with my own medications and my colostomy bag. So, on the Saturday, they moved me to bed C5. Which was nowhere near a window.

But, I was only there for a couple of days, before I was allowed to go home on Monday 21st December 2015. More than two weeks after the liver resection for my recurrence.

At this point, I should point out the pressure all this put on Julie, and how amazingly she handled it. She was having to: run the business, look after the house and the cooking, deal with all the Christmas related stuff that the girls’ school were putting on, and do all the preparations and shopping for Christmas. I don’t know how she coped, but she did.

On another note, it really does pay to keep your weight under control. While some of the complications I faced were likely due to the length of the surgery, my weight was certainly a contributing factor. I wish I had a solution for this but I don’t when I’m stressed, I eat. When I stress eat, I put on weight.

At this point (2018), I’m seriously thinking about seeing a hypnotherapist to see if there might me an answer there. If I do, I’ll report how it goes.

4 thoughts on “Liver Resection For My Recurrence of Bowel Cancer”

Paul I am dealing with multiple health issues with an unknown future, I have two girls 4 and 8 and your blogs give me inspiration that perhaps I will make it to see them grow older inspite of everything else.

Hi Ananya,

I’m really sorry to see that you’re in poor health, and that you and your girls are having to face such a difficult time.

I’ve struggled with thoughts of how much, or little, time I might have with my girls. I’ve done better than some of the estimates I made when I was feeling at my lowest. I’m now feeling optimistic about making another one or two of those milestones.

If it can happen for me, I think you have every right to feel it can happen for you, too.

In the meantime, I’m here if you want to talk about anything.

My best wishes to you all,

Paul.

How tell your 12 daughter you have a cancer and your death will be awfull?

Hi there,

my 12 year old already knew about cancer and understood that having cancer didn’t automatically lead to death. By the time she was 12, for example, she knew that my dad had come through a bout of cancer pretty well unscathed. Mind you, she also knew that his mum had died from cancer, so she knew that cancer was dangerous.

What I told her was as much of the truth as I thought she needed to know at the time. I explained that I had a nasty case of cancer and that I was being treated as ‘curative’. Which was true: the oncologists and consultants were telling me that they thought they could cure me. Now, while I didn’t necessarily share their optimism, I felt no need to share my doubts with my daughter. And, sure, my doubts turned out to have good reason, in that I’m now being treated as palliative, but I am still being treated. And, obviously, I am still here.

As to the potential awfulness of my death; I made no mention of that possibility. If my death does turn out to be awful, that’s something that we’ll all have to deal with when I get to it. There seems absolutely no point in dwelling on the way I leave this world as to do so would add nothing to my life. There’s also nothing I can do to alter the form my death takes, so there’s no point worrying about it.

When my daughter was 12, I told her everything she needed to know to understand what I, and our whole family, would be going through. My daughters are now 16 and 18, and have spent 6 years helping me deal with my cancer. And, while this has certainly taken a toll on them, they’ve coped remarkably well. The older one will leave for University, In September, to study pharmacy. The younger one will leave the following year to study architecture.

If I’d sat them down and laid out how bad things might be, and how awful my death might be, when they were 10 and 12, I’m not sure they’d be on the same educational path.

I hope this makes sense to people other than me…

All the best,

Paul