My third recurrence of bowel cancer, in February 2018, took the form of a tumour in my liver and another in my lung. The liver tumour was successfully removed in May, and the focus then turned towards lung surgery for my bowel cancer metastasis. In preparation for this, my oncologist ordered up a lung function test and sent me off for another PET/CT scan…

Warning: this post contains graphic surgery related images

I had the scan on the 5th June and didn’t really think anything of it. The point of the scan was to check on the progress of the lung tumour, for the benefit of the thoracic surgeon who would perform the lung surgery on my bowel cancer. I was more concerned about the date of the lung function test, which had been organised for 28th June.

My concern with this date was that it was so late on in June, which could have a knock-on effect on the timing of the surgery. If the results of the test took a couple of weeks to process, and then the surgery was a couple of weeks after that, there would be no time for a family holiday over the summer. I know this seems like a strange thing to be worried about, given I’m talking about lung surgery for my bowel cancer, but I’d been facing these sort of choices for four years, by this stage. And it’s amazing what you can get used to. Besides, the whole point of battling the cancer was to spend more time with Julie and the girls. Meaning family holidays are very important to me.

Anyway, with all that in mind, I called the colorectal support team at the hospital and spoke to one of the Colorectal Nurse Specialists. She listened to my concerns and then trumped them. She explained that there may well be changes to the proposed schedule, because the PET/CT scan had reveled, ‘a hotspot in my Thyroid‘!

The implications of this development were discussed, but I’ll cover my adventures with my Thyroid gland in my next post. This post is about the lung surgery for my lung metastasis. Suffice it to say, though, the news about this Thyroid hotspot completely freaked me out.

The same day I was given this news, my oncologist wrote to the thoracic surgeon, in Bristol, asking him to see me. Two days later, on Thursday 14th June, I got a call from the hospital in Bristol saying that, unfortunately, the thoracic surgeon was away for a couple of weeks. But he could fit me in that day, at 3:30 pm… So Julie ditched work and we piled into the car and headed up to meet the thoracic surgeon.

And a fascinating meeting it was, too. For a start, it was a couple of weeks before my appointment for the lung function test. And I’d definitely need a lung function test before the thoracic surgeon could assess my case. Knowing this, he had a lung function machine ready and waiting in the consultation room. And he performed the tests right there and then. This guy was organised!

Fair warning, I’m about to get insufferably smug…

The report came back:

“His FEV1 was 4.3L and his FVC was 5.65L. Both these values were better than predicted.”

He said that there were both about 10% above average. Initially I was a little disappointed with that, because I was deep into training for the Three Peaks Challenge. Then Julie pointed out, ‘well, you do have a tumour in there!’ And the smugness was on…

More importantly, the thoracic surgeon was happy with the result because it meant, and I quote, “I can do what I like with you”. This came across far less creepy than it reads.

Basically, the lung surgery for my bowel cancer metastasis was a go.

The tumour was in the lingula segment of the upper lobe of my left lung. Somewhat confusingly, this meant that the tumour was located right at the base of my left lung, near the diaphragm. This, however, was excellent news, because it meant that the lung surgery for my bowel cancer could be done with keyhole surgery. All he would need to do was make three small incisions under my left armpit, and go in through the ribs.

To get through the ribs, the intercostal muscles, which run between the ribs, would be teased away from the lower ribs, to allow access for the instruments. He warned that the intercostal nerves run along the underside of the ribs and that there might be some temporary damage to the nerves above the entry sites, from the manipulation of the surgical instruments. He also said that there was virtually a 100% survival rate from this surgery, so some temporary nerve damage seemed a small price to pay. Besides, because I’m quite large in stature, there was less chance of damage because there’s more room to maneuver. With someone Julie’s size, there’d be more to be worried about.

Looking forward, the surgeon warned me that when there is one lung metastasis from bowel cancer, there is a 50% chance that there will be another. To this end, he explained, he’d be removing as little lung tissue as possible to allow for further surgeries. Despite this fairly unsettling development, I found the meeting very reassuring and felt in good hands.

The date of the surgery was arranged as 11th July. It was a bit later than it needed to be, to allow me time to accompany Emma, my older daughter, on her attempt on the Three Peaks. At least I’d be good and fit for the lung surgery for my bowel cancer tumour. Better still, my admission time was midday, meaning I could even have a lie in…

Come the 11th, while I was waiting for the surgery to kick off, I had a visit from the physiotherapist. She gave be a gauge, through which I had to inhale. The gauge went up to 4,000 ml and had a little smiley face indicating the rate in which you had to inhale. Which was much slower than you’d like.

Anyway, I maxed it!

Hell, yeah; I’m smug about it. But that’s nothing compared to what’s coming later…!

The physiotherapist then told me that she’d be checking me against this baseline, the day after the surgery. In order to prepare for this, she gave me a series of breathing exercises to practice while I was recovering. Fair enough, I’d give it a shot.

After that, I had a visit from the surgeon and the anaesthetist. I was warned that I might wake up with a sore throat because of the way I would need to be intubated. Essentially, as soon as the incision was made for the lung surgery for my bowel cancer, my lungs would collapse. To counter this, the intubation tube, through which I’d be breathing, would have to go all the way down into my right trachea. At this point, a cuff on the tube would be inflated to maintain an airtight seal. Then my right lung could be worked to keep me breathing. Anyway, all that had to be shoved down my throat, past my vocal cords, hence the possibility of soreness.

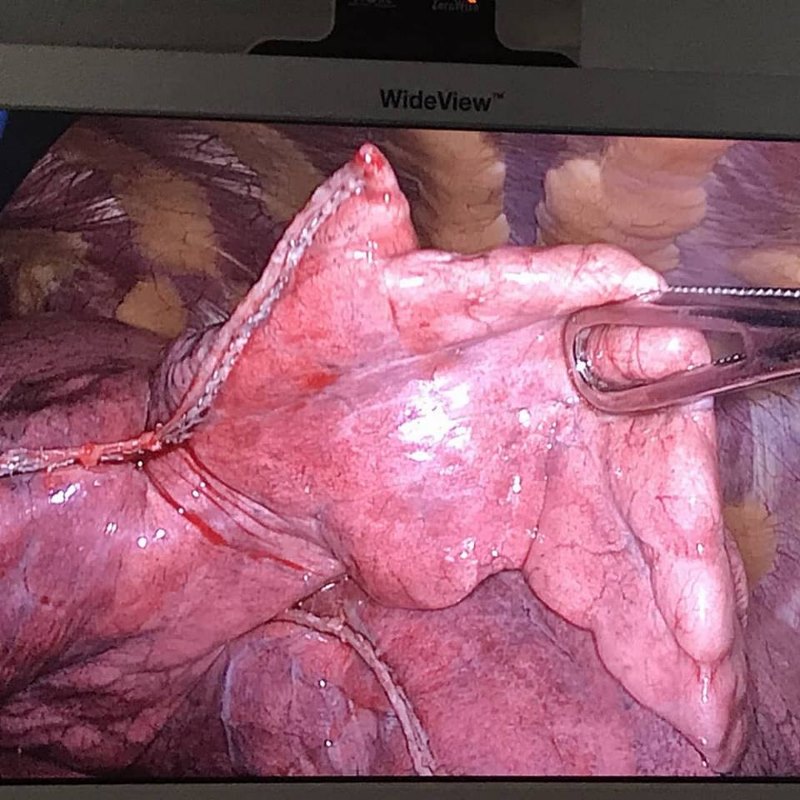

Then we got on to the really important stuff: the need for a gory photo. I explained that the liver team had managed to get me some good photos over the years, and the thoracic team was on board. Challenge accepted! I was quite excited about what I might get, and I wasn’t disappointed…

The actual process of the surgery was new and exciting as well. I was fitted up with my cannulas outside the theatre, as normal. Then I got to walk in and arrange myself on the operating table. I’d never seen the inside of a theatre before. It was big, light and airy, which I found a bit surprising really. The reason I had to get on to the bed myself, was that I needed to be on my side during the lung surgery for my bowel cancer, with my arm above my head. This gave the best access to my ribs and maneuvering an unconscious patient into the right position is tricky. Once I was out, the bed would actually be lowered at each end, to stretch the ribs out a bit more. This decreased the risk of nerve damage. But I slept through that bit.

In fact, I slept through quite a lot. Or, at least, it seems like it: I have virtually no memories of the hours after the surgery. I had to ask Julie what happened, to write it up in my journal. Apparently I woke up in Recovery, and had a chat with the surgeon. He explained that the lung surgery for my bowel cancer had gone really well. An hour, or so, later I was wheeled back to my room, where Julie was waiting. Even now, I remember none of this.

What I do remember is that I had a cannula in each arm, a drain in my chest and no urinary catheter. The lack of a catheter was good, although it did mean I had to wee into cardboard bottles for the rest of my stay. The drain was awkward and uncomfortable, without being painful. It did make sleeping difficult. Or, it least, it would have, if I wasn’t right next to the nurses station. The half-hourly bleeping, of other patients calling nurses, made meaningful sleep impossible.

I took the opportunity, while I was not sleeping, to work on my breathing exercises. This involved taking a series of progressively deeper breaths, in sets of threes, until I was taking as deep a breath as I could, and holding it. It was a fairly painful process, especially at the beginning. But got easier with practice. The pain was totally worth it when the physiotherapist came in and asked me to inhale through the gauge. Roofed it again! Boom! Smugness overload.

In fairness, she didn’t ask me to control the rate of inhalation, making it much easier to achieve. Even so, she said that she had another patient who’d been operated on 10 days ago and could still only get to 2,000 ml. She then took me for a walk and asked me if I felt up to walking up a flight of stairs. As I came back down, I explained that I’d had a visitor earlier and, when he left, I walked him back to his car. A journey that involved going up and down three flights of stairs. She signed me off at that point. She also let me keep the gauge. I like my gauge…

I should point out that while I am being flippant and smug about this, I’m aware that it’s mainly down to luck, on my part. It just so happens that I recover well from surgeries. I’m also fairly young and fit, compared to other patients having this type of surgery. Expect recovery to take a while, although do push yourself with the breathing exercises. Even though it hurts. Doing so will increase your rate of recovery and lower your chances of complications.

After lunch, the thoracic surgeon paid me a visit. The drain was pretty much empty so he decided to take it out and then send me home. Result!

The drain was stitched in place, so he cut the stitch and then told me to take a deep breath and then keep breathing out while he withdrew the tube. I imagined that a collapsed lung was on offer, if I got it wrong, so I kept breathing out for as long as I could. Once the tube was out, he drew the wound closed with another stitch, which was already in place for just this reason. The tube was surprisingly long, which explained why it was so uncomfortable.

But that was that… the lung surgery for my bowel cancer tumour was officially over. The surgeon went to get the paperwork started and, shortly afterwards, a nurse came in and removed the cannulas. Rather than drag Julie out of work, my parents offered to come get me. I had a shower while I waited and was home in time for dinner.

The ongoing recovery at home was the most tricky of my keyhole surgery operations. It was difficult to lie comfortably on my bed. I used my ‘V’ shaped pillows to prop me up for a couple of days, but it’s difficult to get any real sleep on those. Laying on my right side was just about bearable. Laying on my left side was too painful to contemplate for at least a week.

Part of the reason it took so long was, after four days, I tried to get comfortable on my left side, through the pain. I just managed to relax when I experienced an incredibly sharp pain from the site of the main wound. It felt like I’d been stabbed. On reflection, I think I know what happened… the muscle that had been teased away from my rib had just about reattached itself. Until I lay on it and relaxed. At which point it was torn away again. I didn’t do that twice!

Photo by Thanh Tran on Unsplash

Aside from the pain when I was trying to sleep, it quickly became clear that at least one of the intercostal nerves had been damaged. I was numb around my armpit. Worse, was the feeling of my flesh crawling in the area on my back, behind the armpit. In addition, there was discomfort in my left triceps that took weeks to clear up. Everything did clear up in the end though.

And, as for the pain, it only lasted a while. Apart from when the intercostal muscle separated from the rib, I only took paracetamol. Even when the muscle went, I only needed ibuprofen a couple of times. Within a week, I was only taking paracetamol at night, to help me off to sleep. A few days after that, I was drug free. Despite this relative lack of medication, I did end up with some pretty epic constipation for a while. But even that resolved within a couple of weeks of the operation.

The stitch from the drain came out 10 days after the liver surgery for my bowel cancer metastasis. And the scars healed up slowly but surely. Leaving me fully focused on finding out just what the Hell was going on in my Thyroid…