During the research for my posts on Complementary and Alternative cancer therapies, I realised that the traditional conventional cancer treatments had moved on a bit since I last had any. This means that it’s high time I found out what’s going to be in store for me next time I need something other than surgery.

In my post on complementary therapies, I explained conventional cancer therapies as follows:

These are the types of treatments that are offered by doctors, hospitals and scientists. They are the types of treatment that have been shown to be the most effective, during human testing and in peer-reviewed studies. They also show the best results in treating cancer patients.

http://www.cancerdad.co.uk/what-are-complementary-cancer-therapies/

In contrast, complementary and alternative treatments are those that have either not been shown to work, or have been shown not to work. While there is some crossover between complementary and alternative treatments, they can be best thought of like this:

- Complementary treatments are used alongside conventional cancer therapies

- Alternative treatments are used instead of conventional cancer therapies.

So, while neither of these non-conventional options have been shown to have much in the way of a benefit, complementary treatments sit alongside what the Doctor orders. As such, even if they’re not actively helping, they’re not getting in the way. Alternative treatments are used instead of conventional treatments, which means that not only are you taking the stuff that doesn’t help, you’re not taking the stuff that does help.

My contempt for anyone who pushes people away from conventional cancer therapies into alternative treatments, knows no bounds. These people are shortening the lives of cancer patients and should be made accountable for their actions…

But, let’s not go there again.

In the previous post, I made a list of conventional cancer therapies, which was as follows:

Of these, the top three are what would be considered the traditional conventional cancer therapies, which I’ll cover in this post. The remaining, newer, conventional treatments will be discussed in a separate post to prevent an information overload.

For many people, the traditional conventional cancer therapies are thought of as: Slash, Burn and Poison. The terms are used in a derogatory manner, which is ironic because, with the exception of ‘Slash’, they’re pretty damn accurate. ‘Slash’, however, is idiotic because it implies a lack of control. The surgeons are, of course, very much in control. They should have gone with ‘Slice’ instead.

As far I know, they haven’t managed to come up with anything belittling for the newer stuff yet. Let’s hope that more thought than ‘Slash’ goes into whatever they end up with…

The simple fact of the matter is; of all the traditional and new conventional cancer therapies, surgery is your best chance of a cure. No matter what you choose to call it.

And, yes, I do mean, ‘Cure’!

Doctors, oncologists, consultants and surgeons are all very reluctant to use the word ‘Cure’ when they’re talking about cancer treatments. They’ll happily talk about Remission, which is when you’ve remained cancer free for a certain period of time. Usually five years. But ‘remission’ isn’t the same as ‘cure’, although it’s usually as close as anyone is going to hear.

Despite that, there’s an unavoidable truth: if all the cancer cells have been cut out of your body, you no longer have cancer. You’re cured!

This is why surgery remains the Gold Standard of traditional conventional cancer therapies. If a tumour has not spread to another part of the body (metastasised) and can be completely removed (with clear margins), providing the surgery goes well, you’re done. Your cancer journey is over. You won.

Even if the cancer has spread, if the metastases can be completely removed as well, you’re still done and dusted. Although you’ll probably be given chemotherapy as well, for reasons I’ll get into shortly.

If, however, the surgery damaged the tumour, or the surgeon couldn’t achieve clear margins, or the tumours aren’t operable; you’re going to need other options. And I’m going to start with Chemotherapy because, of the traditional conventional cancer therapies, I’ve had personal experience of that one.

Chemotherapy literally means chemical therapy. The chemicals in questions are just a wide range of medicines. So chemotherapy is just another way of saying medicine therapy. Or drug treatment. Just like you’d receive for endless other diseases and conditions out there. It’s worth remembering that chemotherapy is just medicine. But, also, that it is a poison.

Medical staff know this. Cancer patients know this. So, if you feel compelled to shout in someone’s face about how, ‘chemotherapy is a poison’, like you’ve just discovered displacement, understand that we all know this. We know chemotherapy is a poison and we take it anyway because, you know what? It works. Not all the time. Not for everyone. But enough to mean that for most people, most of the time, taking chemotherapy is a better option than not taking it.

I’m not going to go into the full pros and cons of whether chemotherapy can cure cancer, because I’ve already written about that and you can read about it here. What I will say is that taking chemotherapy sucks, and I hate the stuff. But that, without it, I’d be long dead. So the real question is, would I take it again?

Yes, in a heartbeat.

Each type of cancer, of which there are over 100, has its own specific chemotherapy regime. As such, I can’t go into them all, here. Instead I’ll focus on the one I’m most familiar with, bowel (colon/colorectal) cancer.

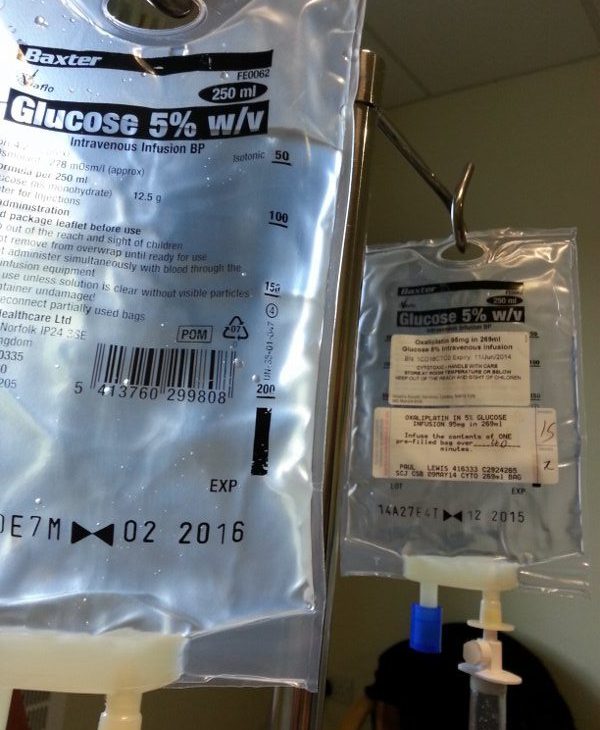

The first line of chemotherapy for bowel cancer is Oxaliplatin, intravenously, and Capecitabine, as tablets. These are used to debulk (shrink) and/or destroy the cancer cells. As such, you might receive this treatment before surgery, to ensure the tumours are a manageable size. You might however, be given these drugs after the surgery, to mop up any cancer cells that are floating around the body. Or both. I had three month treatments either side of my surgeries.

For some people, this chemotherapy can completely stop a cancer in its tracks. For others, it has little to no effect. I fell into the latter category. This form of chemotherapy is used during curative treatment, which is to say when there is the expectation that the cancer can be cured.

When curative treatment is no longer an option, you’re moved on to palliative care. Generally speaking, ‘Palliative Care’ means ‘End of Life Care’. In cancer treatment, this isn’t the case. In cancer treatment, ‘Palliative Care’ simply means ‘Non-Curative Care’. It’s a subtle but important distinction. I, for example, have been receiving palliative care since 2016, which means that the hospital expects my cancer to be terminal.

So, how has this move to palliative care effected my treatment?

Not in the slightest!

Admittedly I was given a different type of chemotherapy. FOLFIRI, instead of Oxiliplatin and Capecitabine. But I was still given chemotherapy. And, although the FOLFIRI is more expected to knock the cancer back than destroy it, the treatment worked extremely well in my case. So much so that, at the time of writing (April 2019), the liver metastases I had in 2016 have not returned. The one in my lung did, but I’ll get on to that.

In 2017, despite being on palliative care, my stoma was reversed, meaning I no longer had a colostomy bag. Then, in 2018, when my lung metastasis returned, along with a new tumour in my liver and a questionable lump in my thyroid, I was given surgery. Three surgeries, actually. First my lung metastasis was removed. Then I had a liver resection for the latest tumour there. Finally, I had a hemithyroidectomy, to address the lump in my thyroid, which turned out to be benign.

So, yeah, ‘Palliative Pare’ does not mean that anyone has given up on you. It doesn’t mean that anyone is expecting you to die any time soon. It means that you’re most likely non-curative and that has implications on the treatment you need. No matter what happens, the priority of the hospital will be to act in the best interest of the patient. Providing you keep yourself as fit and healthy as you can, your best interest will be; all the treatment you can handle. Be it surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy or whatever…

Briefly coming back to palliative chemotherapy for colon cancer, it seems there is a new kid on the block in the UK. Raltitrexed! It sounds just as poisonous as the other types of chemotherapy but it’s nice to know that there’s another option out there.

And that’s essentially the principle of chemotherapy. Each cancer type has its own range of curative and palliative chemotherapy options. However, everyone is different, which means that the effectiveness of each chemotherapy type differs from person to person. For me, the Oxiliplatin and Capecitabine treatment was rubbish, while FOLFIRI was amazing. Not the side effects: the side effects of both sucked! I have no idea how I’ll respond to Raltitrexed? I’ll let you know if I ever find out.

The important thing, though, is that chemotherapy is far from the only treatment option available. Next there’s the last of the traditional conventional cancer therapies: radiotherapy.

Historically, radiotherapy has worked by firing a beam of Ionising radiation through a tumour.

In terms of ‘Burning’; yes it does. Perhaps the best ‘Burn’ analogy is to imagine someone shoving a red hot needle all the way through your body. As you’d expect, the ‘needle’ kills all the tissue is passes through. This means that it kills healthy tissue as well as the cancer cells.

Pretty horrific, right? You know, apart from the bit where it’s killing the cancer cells.

Radiotherapy can absolutely save your life.

Sure, there a bunch of nasty side effects, including burns to the area of skin through which the beam of radiation passed. But the side effects usually clear up after a couple of weeks. At which point, you’re better off than you were. Which sounds worth it to me.

Not that this type of radiotherapy is much of an option for colon cancer. For beams of radiation to work, the tumour needs to be in a relatively fixed location in the body. So there can be an element of certainly that the the beam of ionising radiation is actually hitting the cancer cells. Things like intestines tend to move around too much to make this a viable option. So it’s just as well that there are plenty of other radiotherapy options available…

Broadly speaking, radiotherapy can be broken down to two categories: Internal and External Radiotherapy, each of which have several options.

For Internal Radiotherapy, you have:

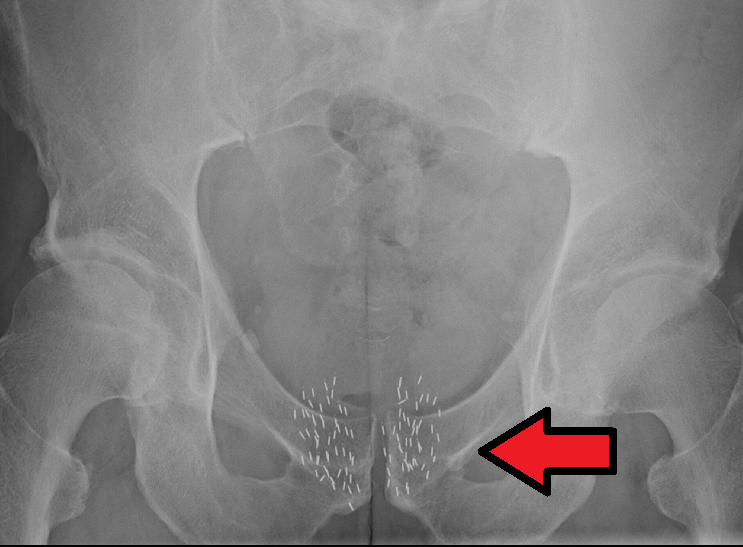

- Brachytherapy, where small radioactive pellets, seeds or wires are implanted directly into a tumour. These implants stay in place for a few minutes to an hour or so, as required, before removal.

- Included in this option is Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (SIRT). This is when radioactive ‘Microspheres’ are put in a blood vessel heading into the liver. The microspheres then get drawn into the blood supply of the tumour where they cause a radioactive blockage, destroying cancer cells. SIRT is of particular interest for me because, as of this month (April 2019), it has become available on the NHS for people with liver metastases stemming from bowel cancer. People like me.

- Nuclear Medicine is where radioactive liquids are introduced into the body to be picked up by cancer cells. The options include:

- Radioactive Iodine Therapy, which is taken as a drink or a capsule and targets thyroid cancer cells.

- Radioactive Phosphorus Therapy, which goes in as an injection and is aimed at cancers of the blood.

- Radium 223 Therapy, another injection, used for bone cancers, specifically those secondary to prostrate cancer.

- Radioactive Strontium Therapy, which is also an injection and also attacks bone cancers.

By James Heilman, MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49068263

In terms of External Radiotherapy, the options include:

- Conformal Radiotherapy, which is the ionising radiation beam, described above.

- Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy, which uses a series of smaller ‘beamlets’ to better target the shape of the cancer.

- Image Guided Radiotherapy is used for tumours that might have shifted slightly between treatments. Things like Prostrate tumours, which can shift depending on how full the bladder is. So scans are made, just before the treatment, and the direction of the beams adjusted accordingly.

- Stereotactic Radiotherapy (SBRT or SABR), uses a series of lower intensity radiation beams introduced into the body along different planes. These beams intersect at the tumour. Only there are they intense enough to cause tissue damage. This process is often for very small tumours and is incredibly accurate.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS), which is the same principle as SABR, but used on the brain.

- Proton Radiotherapy uses protons for the radiation beam, instead of photons or electrons. The protons allow for a very targeted approach, resulting in less damage to the tissues surrounding the cancer.

- Total Body Irradiation (TBI) is for when you need to destroy all the marrow tissue in a person to prepare them for a bone marrow transplant.

As can be seen, there is plenty of variety in the traditional conventional cancer therapies. Better still, there are recent developments for stage 4 bowel cancer patients in both chemotherapy and radiotherapy. You can’t say fairer than that.

I’ve always kinda seen my role as a cancer patient as, living long enough for something that can save me to be developed. So, as well as these new options in the traditional field, the last five years have seen the introduction of a whole new set of conventional treatments. Which I’ll look at next month.