If April 2020 was something of a damp squib, treatment-wise, May 2020 has been anything but. During the first half of May 2020, I made five trips to the Bristol Royal Infirmary (BRI), where I received 50 whole Grays of radiation. Then, during the second half of May 2020, I tried to avoid feeling too sick after what’d happened in the first half…

An interesting month, was May 2020:

- I had a new treatment

- In a new hospital

- And I got introduced to new words like, Gray (which, unlike ‘grey’, is not a colour: you only have to look at my hair to know that I’ve got plenty of experience of grey…*)

The first treatment was on the 1st May 2020, almost as if it had been planned for this update. The BRI is about an hour’s drive from where we live, and Julie would be along for the ride. Partly because it was nice to get to spend a couple of hours with just the two of us, even if it was travelling to and from radiotherapy treatments. Mainly in case I was left feeling too nauseous to drive myself back. The downside of this was that Julie would be stuck in the car for however long my treatment took: the Coronavirus Lockdown was in full effect.

The Coronavirus Lockdown made the whole SABR treatment even more surreal. To start with, I had to check in by phone when I arrived. I would then receive a call back to invite me down to the waiting room. On the first visit, this invitation was immediate. Second time around, I ended up kicking my heels for more than an hour (I’d already left the car in anticipation of being called down, due to parking issues). The other three visits all involved waits of less than half an hour.

The parking was something of a problem, as that part of the BRI was undergoing work. This meant that the usual car parks were full of construction vehicles. On the first trip we got lucky with a space in the nearest remaining car park. Whereas on the second visit we ended up on a residential street, about half a mile away from the hospital (which is why I set off before I was called). For the other trips, as with the wait times, we had outcomes somewhere between those two extremes.

Having been called to the waiting room, I first had to negotiate a COVID-19 desk at the main entrance. Here I was asked whether I was showing symptoms and then had my temperature taken. Once the COVID desk was satisfied, I was allowed to descend the two floors to the waiting room. The seats in the waiting room were all positioned two meters (six feet) apart from each other, which drastically reduced the numbers available. Hence the requirement to wait in the car until called. A very well designed system, I thought.

Having checked in at the desk, I was immediately pounced on by a nurse with a clipboard. She needed me to fill in the details for my insurance company. I didn’t have these to hand because, once again, I’d completely forgotten this was being done privately. Fortunately there was reasonable WiFi access, so I was able to cobble together what I needed.

I think that the main reason that I’d forgotten was that the BRI is clearly an NHS hospital. And the SABR equipment I’d be treated with was, therefore, NHS kit. In fact, the only evidence that anything was being done through the private system, other than the form filling, was the medication.

I got two lots of it…

Shortly after I’d filled in the forms, a nurse came over and handed me a box of Omeprazole and two boxes of Metoclopramide. Almost immediately after she’d talked me through how to take them, a guy rushed in with a bag containing a box of Omeprazole and two boxes of Metoclopramide. I explained that I’d just been given my Meds and he shrugged it off and told me to hang on to them. So I did.

Which later turned out to be just as well…

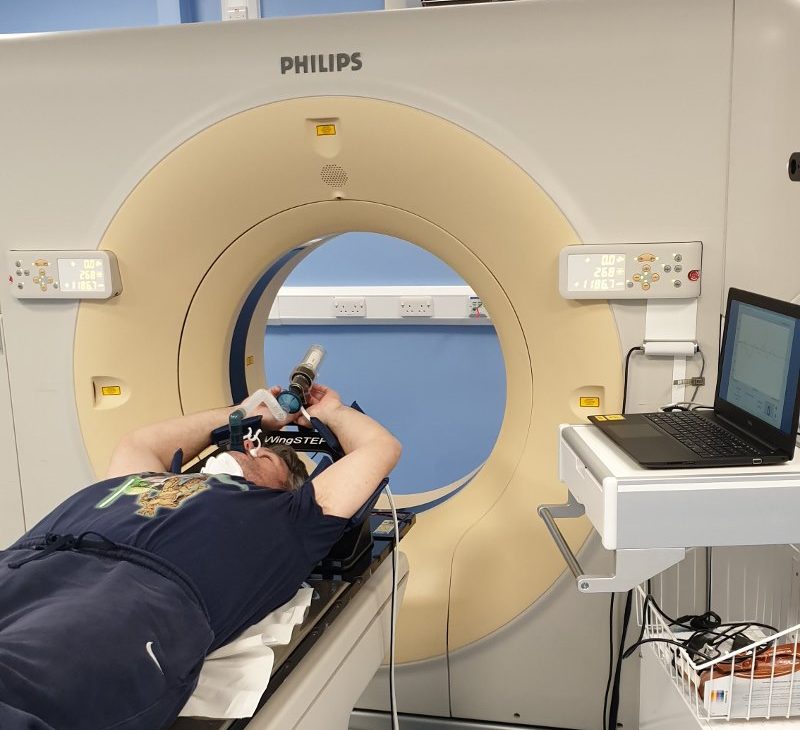

When I’d done my breathing training for SABR, back in April, I was taken to a room off to the left of the waiting area. So I was somewhat surprised to be called over to a room to the right, this time around. As I went through my treatment, I worked out that the machine I was put on, for that first visit, wasn’t actually a SABR machine. It was simply a CT Scanner, with a mock up of the SABR breathing system. Which is how they were able to scan me with contrast, after the training.

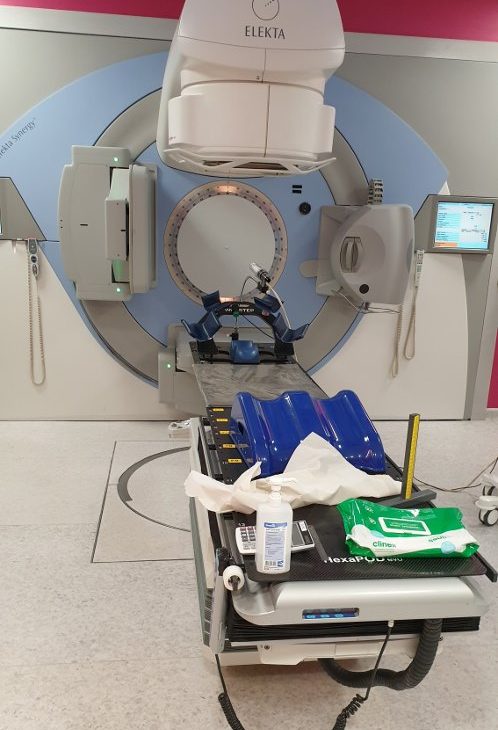

The SABR machine itself was a different beast altogether.

For a start, a CT scanner is designed as a torus, which the bed passes through. The SABR machine, on the other hand, has four arms, at 90 degrees from each other, which rotate around the bed. It’s a bit like being in an incredibly slow mixer…

I’ll go into the finer details of what’s involved in ABC SABR in a dedicated post. So I’ll only do the edited highlights here…

If you remember, I was given three new tattoos during my April visit? Well, they needed to see those, so it was off with the shirt. Then it was all about being arranged in a precise position on the bed. The bed covering is made of plastic, which means your skin sticks to it after a while, which is exactly what they’re after. Once you’re in place, there is no moving. Seriously: no moving!

The ‘precise position’ in question involved me laying on the bed with my arms above my head. There were arm supports, both above and below the elbow, so there was no stress or strain involved. A pad was also placed under my knees to minimise any pressure there. Once I relaxed into place, I had a control put in my hand, such that my thumb could press the button. After which the breathing tube was offered up and, once that was comfortable, a nose clip put in place.

The tattoos were then used to line my body up with the lasers. This did involve a rather small nurse trying to shove my somewhat sizable torso across the bed a fraction, while telling me not to help her. She didn’t want me to move myself as I would just disrupt the rest of my positioning. But my skin was already adhered to the plastic, so she had no chance!

Turned out not to matter, which was good.

I was told that there’d be a CT scan first, and then the treatment would start. The nurses left the room.

And then we were off…

The machine couldn’t work if I wasn’t pressing the button. So every breath hold started with, “If you’re ready, press the button.” Or words to that effect.

So I’d press the button and breathe away.

As I started an inhalation, I’d be told, “On your next breath, take a short breath and then a deep breath, in and out.”

Actually, I don’t think I’ve got the words exactly right. I can’t believe that I can’t be sure of the exact expression, given the number of times I heard it during May 2020!

Oh well, it’s not that important; I’m sure you get the gist…

Anyway, that’s what I did: a short breath, followed immediately by a deep breath, in and out. Except the breathing tube locked up after three quarters of the exhalation. And then the counted started over the intercom: “Twenty four, twenty three, twenty two…”

All the way down to “one”, at which point I was told to breathe normally. And this was done on ever single breath hold. There was always a nurse with you, literally every second of the way.

My first scan took just over two breath holds. One of the nurses came back in, immediately and told me they needed to do the CT scan differently. This did not surprise me. In my case, CT scans are never that effective, no matter what my weight is. It seems that my liver is quite dense.

Anyway, back to square one. This time the scan took just over three breath holds.

Then there was a pause…

With each visit, this pause varied in time. Although, as ever, it was the second one that dragged on the longest. There was no way of marking the passing of time, as there were no clocks visible. And there was no communication from the nurses. But I knew that all I had to do was lie still and not move. Something, which if I do say so myself, I’m particularly good at!

And, in due course, the bed moved. What’s happening during the pause is that the CT scan is being studied to ensure that the tumour is lined up perfectly with the machine. As such, the bed can be adjusted in all three planes. There was always an adjustment at the end of this pause, and then the CT scan was repeated. Only then was I ready to start my treatment.

After the second CT scan, there came something of a whirring noise. Where, presumably, some expensive piece of kit was moving into place. And then exactly the same thing happened as with the CT scan: the four arms of the machine slowly rotated around me, while I held my breath. The treatment phase took nearly four breath holds. The only noticeable difference with the treatment, compared to the CT scan, was that the arms shuddered to a stop during the treatment phase. They came to a much smoother stop during the CT scans.

Speaking of CT scans, that’s what comes next. There were two rounds of the treatment phase and, in between, there was another CT scan. This was to ensure that I hadn’t moved during the first stage of the treatment.

And, as I didn’t move during the first stage of the treatment, for any of my first three visits, I didn’t get this second CT scan phase during my last two visits. Which speeded things up nicely.

What also helped speed things up was that I mentioned that I could hold my breath for 30 seconds, if that was preferable. I’d noticed that a number of the scans and treatments had involved a very short breath hold at the end. So, I figured that if I was holding my breath for an extra five seconds each time, this would reduce the total number of times I’d have to hold my breath. I mentioned this to the nurse who was cleaning down the equipment, at the end of my first visit. He said he’d pass it on…

Which he did.

And, from the second visit onward, I was holding my breath for 30 seconds at a time. One of the nurses did mention that my being able to do 30 second breath holds was helpful, as it made the whole process that much quicker. Which I was very glad of as, by that stage, I was feeling somewhat guilty for being there at all. What with me being done privately. What if I was bumping someone who needed it more?

And, while I understood that the whole private system was also under NHS control, making this extremely unlikely, I felt that by being as quick as possible, more people could go through the treatment.

That said, if you’re facing SABR yourself, please be aware that the standard breath hold is only 20 seconds. Additionally, the nursing staff are very aware that some people have breathing issues that mean they can only manage 10 seconds at a time. Someone like me, who can manage 30 second holds, just balances out the timings.

Anyway, in total, during that first visit, I did 23 breath holds. This number dropped for the second and third visits, after I moved up to 30 second breath holds. And dropped again for the final two visits, when the latter CT scan was removed.

At the end of each visit, I was invited to sit up slowly: there was a very real risk of a head rush, after laying still for so long. Then it was just a case of getting dressed and heading home…

And waiting to see if I’d feel sick…

Which I did. But not nearly as badly as I thought I might. Thanks, I think, to the Meds I was given, both of which were antiemetics: designed to stop me feeling sick. I was to take one Omeprazole a day, for 28 days, which would give a base level of protection for my stomach lining. The Metoclopramide was to be taken with meals and give more immediate relief, as needed.

I started off taking three Metoclopramide a day but later into May 2020, when I forgot a couple of tablets with no ill effect, I started cutting back. I was off the Metoclopramide long before the end of May 2020.

The Omeprazole, on the other hand, was very effective. I finished my 28 day course, as instructed, which took me right to the end of May 2020. Great, except that I started June feeling really quite sick. Thankfully, though, I had that second packet of Omeprazole, which I took for the first five days of June. I haven’t taken anything for a couple of days now, and have experienced no ill effects…

All of which, both rounds off my treatment in May 2020, and explains why this update is a week later than I wanted. Sorry about that but it seemed the most sensible option.

I had known that, due to the closeness of the tumour to my stomach, the SABR treatment would lead to an element of nausea. In reality, though, this nausea was nothing compared to what I experienced during chemotherapy. Either of my chemotherapies! Furthermore, I didn’t get any skin irritation at all, something that I was frequently warned about.

In fact, the only side effects, other than the mild nausea, were fatigue and temporary bloating. Both of which I did get a lot of. I was told that the worst of my symptoms would appear a week to ten days after my final treatment. Things would then take a week or two to get back to normal. I decided that this would coincide with the last day of May 2020 because I really needed to start a diet!

Ever since I was told that I’d had another recurrence, back in February 2020, I’ve been piling on the weight. The self pity party that I’ve been indulging in, throughout the entirety of May 2020, has been the icing on the cake (pun intended). I’d hoped that at least some of my newly acquired weight would be down to the bloating…

This was very much not the case!

And, so, June 2020 started with another diet. I’ve decided to spend the next four months losing the three stone (42 lb, 19 kg) I’ve gained since my diagnosis. After that: who knows?! I have an appointment with the SABR consultant on 20th June, which I’ll report back on at the end of the month. I presume that part of this meeting will be to book me in for another set of scans, to see how the treatment has taken…

I can only hope that whatever these scans reveal, aren’t enough to derail my weight loss.

The main issue relates to when I was moved on to palliative care back in 2016. At that point, I was told that I had two to three years to live.

Pah! I mock your prognosis…

However, after I outlived this original prediction, it was suggested that it had become a rolling prognosis. A prognosis which could kick in at any given time, hence all the stress when I’m waiting for scan results.

But the real problem is that it’s only possible to work out the start date of this prognosis, retrospectively. Meaning that I could already be nearly six months into my final two to three years…

Still, it’s worth remembering that all of this is gravy.

Had the original prognosis been right, I’d have been gone more than a year back. And you wouldn’t have to read all this self-indulgent twaddle.

Yet, here we all are…

Stay safe.

* I was sorely tempted to say, “you only have to look at my wife’s hair to know that I’ve got plenty of experience of grey”, but you can only take so many chances before it all catches up with you…!

1 thought on “Progress Update for May 2020”

Well Bravo for getting through all of that! And thanks for the extensive and informative update. Everyone deserves a medal for getting through covid and the last three months, but yours should certainly be a Gold one! Hang in there!