Since the start of the Coronavirus Lockdown, people have had a lot of time on their hands. People are stuck at home and they finally have time to do all those things they keep meaning to do, but never have the time. One of the most popular Lockdown activities seems to have been baking. In particular, bread. Even more specifically, Sourdough bread: a ‘real bread’!

But what is a real bread? And, conversely, what isn’t?

Well, I think the one thing that we can all agree on, is that the mass-produced stuff you get in the supermarkets isn’t real bread. Not even close! I think I once heard Paul Holleywood refer to these mass-produced loaves as being more like sponge than bread. I’ve heard other people say similar things…

And, to be fair, I’m not sure I get it. Is the ‘sponge’ in question a baked product, like a Victoria sponge? Because I don’t see the similarity. Cake sponge is nothing like mass-produced bread, to my mind. Alternatively, is the reference in relation to the type of sponge you might find in the sea, or in your bath? In which case… Maybe, I guess…? Although, I’ve never tried toasting a bath sponge, but don’t imagine it would end well.

Anyway, no question: mass-produced loaves, particularly if they’re made through the Chorleywood Bread Process, cannot be real bread:

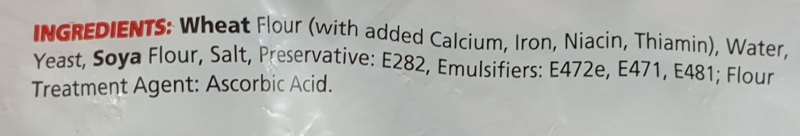

And I’m not trying to pick on Hovis in particular, here. This is just the loaf we had in the house at the time I was writing this post. Although, to be fair, the packaging does say that Hovis has been around since 1886, which means they must be doing something right. Furthermore, 98% of bread baked in the UK is mass-produced, seemingly meaning that an awful lot of people like this type of loaf. Also worth considering is that 80% of the UK’s bread is made using the Chorleywood Bread Process, which I will come back to…

But, whatever! Sponge isn’t bread, so none of this stuff can be real bread.

So, having established what clearly isn’t real bread, it’s time to decide what is. And, to do that, we need an understanding of the origins of bread itself.

Bread has been around for many thousands of years. Maybe even tens of thousands of years. To quote Wikipedia:

The world’s oldest evidence of bread-making has been found in a 14,500-year-old Natufian site in Jordan’s northeastern desert.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bread

Not that the bread made during that time would be considered real bread today. In fact, it probably wouldn’t be recognised as bread at all. The first breads were made by pounding a starchy foodstuff into a meal and then mixing it with water. The resulting ‘dough’ could then be cooked on a hot surface, like a flat stone next to a fire, resulting in a form of flatbread.

In a lot of places the source of this starchy material might be the roots of certain plants. But this is Britain, damn it, so I’m going to talk about Oak trees. Yes, ancient Britons made their bread with the meal produced from acorns. Presumably acorns that had been well soaked first, because those things are bitter!

But, whatever people used as the source of their starch, they used it widely and often. This process of mixing a starchy meal with water and then cooking it to make bread was independently discovered by so many groups of humans, all across the world. The best of these breads, of course, were the ones that bound together well. And the best of these were made using grain. Which is why, since the advent of agriculture, about 10,000 years ago, most bread has been made with grain.

So, if flatbread is the original bread, does this make it the real bread? A tricky question, because flatbread is unleavened, a bread in only two dimensions: is that enough to make it a real bread?!

By Gilabrand – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11601892

And it didn’t take long for the challenger to emerge…

It was very quickly noticed that uncooked dough, which was left alone for any period of time, tended to start to ferment. They won’t have known why, ten millennia ago, but the reason for this is yeast spores. They’re everywhere! What these ancients did know was that if you cooked a fermented dough, you got a loaf of bread.

A bread in three dimensions!

This was the start of leavened bread and, what we call today, Sourdough bread.

So, does that mean that it’s the Sourdough that is the real bread? The first of the leavened breads.

A lot of people must think so, because it seems everyone is making a Sourdough starter…

In the middle of a pandemic Lockdown when there are real shortages of certain products.

Like flour!

This type of thing really does fascinate me. The way we appear to have an almost herd mentality. So many people seem to have the same idea at around the same time. One after the other, various things get sold out, all over the country:

- Flour

- Vegetable plants and seeds

- Chicken coops

- Swimming pools

I’m not trying to pretend I’m above all this. Far from it. The only reason that I know about all these shortages, is that I’ve tried to go down the same route. Almost invariably too late, because everyone else has thought of it before me…

Except, that is, for Sourdough bread.

For those who don’t know about baking with Sourdough, the first thing you need is a Sourdough Starter. To get this, you mix about 150g of flour with about 250ml of warm water. You give it a good stir and then put it in a container, in a nice warm space. After a while, usually less than a couple of days, it’ll start fermenting. It’s very possible that you first become aware of this by the smell. Which is rarely pleasant. So don’t put the starter in your airing cupboard, if it’s full of damp clothes.

Anyway, once the starter is bubbling away, you feed it by giving it the same again.

By Janus Sandsgaard – Own work, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37054581

Thereafter, you need to feed it once a day until it settles down. For all these subsequent feedings, however, you first throw half of it away, then replace it with another 150g of flour and 250ml of warm water. You can expect this process to go on for at least a week. After which time you will have thrown a good kilogram (2 lb) of flour in the bin…

During a flour shortage…!

And the reason that I haven’t made a sourdough starter? Apart from the wastage, I mean. Is that I made one a few years ago. And it just wasn’t that nice.

The problem with Sourdoughs is that there’s no controlling the yeasts, and various bacteria, that get into the mix to start the fermentation process. You could get lucky and end up with something that produces a bread with a wonderfully nutty flavour. Alternatively, you might get something else. Like I did.

Some of the artisan bakers who make Sourdoughs have had their Starters for years. Some of these starters even have names. Others have numbers, like 17B. Which, to me, indicates that it took at least 17 attempts to get a really nice tasting Sourdough bread…

Which just seems like pretty long odds…

Particularly during a flour shortage…!

But, once you’ve got your Sourdough Starter, you’ve got it for life. Providing you keep feeding it. If you don’t keep adding more flour, on a regular basis, the yeast will have nothing to eat. And if the yeast gets nothing to eat, it dies and your ‘Starter’ becomes ‘Paste’. You can prolong the intervals between feedings by keeping the Starter in the fridge. You can also do this by increasing the ratio of flour in the feeding, such there is more flour and less water. Put that in the fridge and you can go a couple of weeks between feedings.

But the thing about a Sourdough Starter, is that you still have to make the bread. You take some of the starter and then add the rest of the ingredients and then you have to knead and prove the dough. It’s still hard work. It’s still time consuming. It still needs doing every day or two…

Basically, I wonder how many of these Lockdown Sourdough Starters have already been chucked in the bin?

The alternative to the wild yeast of the Sourdough, is tamed yeast. Yeast that comes in a packet or a tin. A yeast that has been specifically chosen because it is known to produce a nice tasting loaf. Yeast like this:

If you take this yeast and mix it with flour, water and salt, in the following proportions, you can make bread:

- 1000g flour

- 10g yeast

- 20g salt

- 600ml water

Bread without any waste at all.

Sure, there is still the time and effort involved. You have to knead the dough for a good 15 minutes, then let it prove for a couple of hours. Then you have to knock it back, shape it and leave it to prove for another hour or so. And the actual baking process takes a little getting used to. But, essentially, you can put together a loaf of a known flavour and quality at a time to suit you, without any ongoing headaches.

And I have baked a few of these loaves while we’ve been on Lockdown. Particularly in those first few weeks, when getting into a supermarket was still a risky venture – given I had a course of Radiotherapy to get through in May 2020. And even if you could get to a supermarket, there was no guarantee there would be bread on the shelves. You could, however, almost certainly guarantee that there wouldn’t be flour.

Fortunately, Emma and I both like baking, so we had a reasonable supply of most ingredients left over from before the Coronavirus Lockdown started.

But I digress.

Specific leavening agents have been around for a long time. Byproducts of the fermentation processes of beer and wine have been used as leavening agents for a very long time. So, is this where we get to real bread? Bread that has a known source of yeast, that allows for a specific product of loaf.

Surely, just because the element of risk about the flavour of the loaf is removed, doesn’t make it any less artisan? I mean, Plenty of fine bakers produce their loaves this way: slowly and surely.

A real bread?!

But, historically, ‘slowly and surely’ hasn’t been enough to feed the masses. And, with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution, there were suddenly a lot of people, in not a lot of space, and they all wanted their daily bread. There was no way that the local bakers could keep up with demand, using the traditional process. And, after 1862, and the arrival of the Aerated Bread Company, they didn’t have to.

The Aerated Bread Company used carbon dioxide dissolved in water to put the bubbles in the dough. There was no need for the slow yeast-based processes at all. This development revolutionised production and dominated the market for a century. But was it real bread, though? As it was before my time, it’s hard to tell.

[I asked my parents and neither of them remembered any significant change to bread in the early 60s, so there can’t have been that big a difference from what we have now…]Anyway, the Aerated stuff was around until 1961, at which point the Chorleywood Bread Process (CBP) took over. CBP, at least, uses yeast. It also uses a variety of other additives to help the dough to survive the process. And the process is hard on the dough!

With the CBP, all these ingredients are mixed together, at very high speed, for just three minutes. Three! The pressure is also varyingly altered to get the bubble size, and thus the crumb texture, right. The dough is given less than 10 minutes to recover from this abuse, which also acts as an element of proving. It’s then cut and shaped and left for less than an hour for the final proof. Then it’s baked for just 17-25 minutes.

CBP goes from flour to a sliced and packaged loaf in three and a half hours. But, as we know, this isn’t real bread. It isn’t bread at all…!

Or is it?!

Surely it’s a bit like bread?! After all, it does have some bready tendencies? There’s a definite air of breadiness about it…

Is this not just the same conceit as I mentioned in my post about the Trouble with Coffee? If you go into a Costa, or some such, you can see the coffee beans in the hopper, waiting to be ground, yet the coffee bores snobs connoisseurs will sneer and declare that Costa doesn’t serve real coffee! Are you sure?! The coffee beans are right there! You can see them being ground!

Is this just a case of bread bores snobs connoisseurs looking down their noses at 98% of all bread in this country? To the vast majority of people, mass-produced bread is real bread. And who’s to say they’re wrong. Sure, a Hovis loaf has more than the four ingredients than the typical loaf I bake, but so does Brioche.

Are you saying that Brioche isn’t a real bread, because it has too many ingredients? If so, I think you should pop over to France and tell the French.

Go ahead, I’ll wait…

Exactly!

For me, and because of the foibles of my mind, flatbreads have to be the real breads, because they were the original breads. But I’ve made a variety of flatbreads in my time, and they’re not what I prefer. Real bread, or not, I don’t want to eat flatbread as my staple.

I’ve also made plenty of breads using dried yeasts, and they’re fine. They’re a bit more calorific than I’d like, given how often I’m on some sort of diet. And they go stale sooo quickly! But it’s nice to make it myself, sometimes, it makes it feel like real bread.

But the bread that I most often eat is Hovis Soft White, medium sliced.

Because I like it!

Sure, it tears easily if you try and spread anything firmer than jam. But it stays fresh for a week and I’m happy with the flavour. And, ultimately, I prefer the convenience of Hovis more than the wholesomeness of home baking. Especially as, overall for me, Hovis has more going for it than home baked.

So, while Hovis might not be ‘real’ bread, it’s the bread I really eat.