I think it’s fair to say that all teenagers, the World over, can struggle to cope with the pressure of their respective education systems. Likewise, the move from Secondary/High School, to whatever comes next, is always going to be challenging. With two teenage daughters currently going through this process, I’ve come to the conclusion that, here in England, the system is particularly bad (this may not be that much of a shock to many people…!), But the pressure on an English teenager to choose the right higher education is ridiculous.

In this post, I’ll be referring to ‘England‘, instead of ‘Great Britain‘ or the ‘United Kingdom‘, because the Scots have decided to do their own thing. Normally, as someone of Welsh and English heritage, I’d take this opportunity to take a pop at the Scots. This is so expected that it’s almost a legal requirement. The problem is, and I don’t know all the facts yet, but it seems horribly likely that the Scottish system is better…

Anyway, when I refer to England, I’m also talking about Wales and Northern Ireland, which, more or less, have the same education system. I just don’t want to repeatedly have to write, ‘England, Wales and Northern Ireland’s’. Besides, the legislation that got us where we are originated in Westminster, so England should accept responsibility.

The English system is so messed up that I’m going to have to define what I mean by ‘Higher Education’, as it applies here…

Generally speaking, Higher Education is the schooling you can choose to move on to, once your compulsory education is complete. It is often considered as tertiary education, coming as it does after primary school and secondary school. It goes a little something like this:

- Primary Education: Primary School, Elementary School, etc

- Secondary Education: Secondary School, High School, etc

- Tertiary Education: University, Colleges, Polytechnics, etc

Of course, this only works where there is a two-stage educational system. Lots of other countries offer lots of other systems, such as the three-stage educational system. This three-stage system will typically have a middle school component between Primary/Elementary School and Secondary/High School. Countries that offer a three-stage system include:

- Canada (in some places)

- Russia

- The United States

- Oh, and England (in some places…!)

That’s right, England can’t even be consistent with the number of stages in its education system.

Look, I don’t want to get bogged down with the number of stages that countries offer in their compulsory education systems. It’s bafflingly complex and largely irrelevant to the bit that comes after the compulsory education. It’s just that in England, we’ve managed to squeeze in an additional stage of education; just to make life difficult.

In England, secondary education finishes with GCSEs at the age of 15-16. Higher Education starts at around 18…

The eagle-eyed among you will have noticed a gap between these ages.

This gap is for ‘Further Education‘, where 16-18 year olds spend two years at ‘College‘ studying their A Levels. This Further education is not compulsory. That said, since 2015, all school leavers must remain in some form of education or vocational training until they’re 18. And, by and large, if you intend to go to university for higher education, you’ll want to do A Levels. The ‘A’ in A Levels stands for ‘Advanced’, as in; General Certificate of Education, Advanced Level. This surely means, however, that the stages of education in England looks like this:

- Primary Education: Primary School (ages 3-11)

- Secondary Education: Secondary School (ages 11-16)

- Tertiary Education: College (ages 16-18)

- Quaternary Education: University (ages 18-21/22)

If you’re thinking that I only wrote that to use the word ‘Quaternary’, well… you might be on to something!

Moving on…

A lot of degrees in England are three year courses. Increasingly, though, four years courses are being offered, particularly if they lead to a specific profession. Architecture degrees, for example, will often involve around a year in placements at architectural firms, taking them up to four years.

Photo by MD Duran on Unsplash

As such, if a teenager anticipates taking on Higher Education, they can expect to stay in education until they’re at least 21. The problem is, that in England, you have to make choices about your degree when you’re only 13 to 14 years old. Which is at the end of Year 9, the third of the five years of Secondary School. Expecting a teenager to know what they’ll want to do for their higher education, at the age of 13, imposes extreme levels of pressure.

In year 9, the teenager must choose the subjects they will study during their last two years of secondary school. These chosen subjects are what the student will sit for their General Certificates of Secondary Education, or GSCEs. Students must choose wisely, because, at age 15 to 16, when it’s time to decide on A levels. It’s their GCSE results that will dictate what A levels are available.

And, of course, the degree courses that you can apply for, at 17 or 18, are extremely dependent on the A levels you take. This really does mean the pressure-filled decisions made by a teenager, as young as 13, have a direct impact on their higher education prospects.

Let’s look at a case study…

A boy gets his year nine results and, chooses his GSCE options on the basis of those with the highest grades. He has a good mark in Biology, so that’s in. His grades in Chemistry and Physics are the same but he prefers the latter, so goes with that (he’s not allowed to do all three sciences!). He goes through years 10 and 11 and passes both courses. As Biology is his favourite subject, he wants to study that at A level, only to be told, “You can’t do a Biology A level without a GCSE in Chemistry!”

So he does the closest A Level to Biology that he can, which is ‘Social Biology’; a version that has little to no Chemistry.

During his A levels, he does his due diligence and finds the perfect degree course, leading to his dream job: Marine Biologist and Oceanographer. He applies to the universities offering this course and they all reject him out of hand!

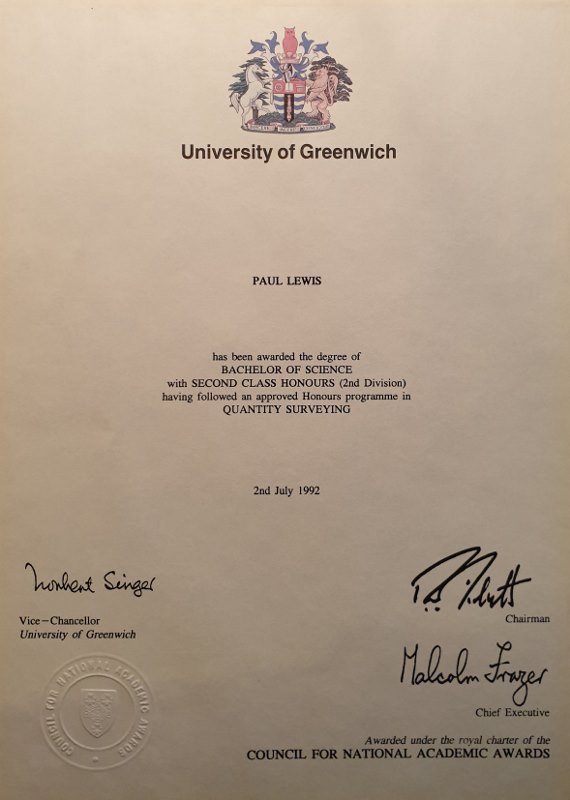

You see, you can’t be a Marine Biologist and/or Oceanographer without chemistry. The uninformed choices made at 14 meant that, at 18, there were no good choices available. So he did a degree in Quantity Surveying.

Quantity Surveying sucks!

You might be wondering why this guy (you know it’s me, right?!) jumped from Marine Biology to Quantity Surveying. Well, the thing you have to understand is; this was in the 80s!

Back then, the Government actually funded students through University. That’s right; I was paid to go to Uni. This meant that my choices were: get a rebound job, or; get paid to study a subject that could lead to a pretty good career.

I chose… neither.

I went to Uni but I didn’t like the course, so I didn’t do much in the way of studying… But that’s a story for another day.

In the here and now, I’ve got Ceri applying to go to college, much as Emma did this time last year. In the meantime, Emma’s applying to Universities. And, these days, the Higher Education experience is a very expensive prospect, which makes those choices made as a young teenager all the more pressure laden.

Is this really the best way to do things? Are there no alternatives?

Well, yes; there are plenty of alternatives. It seems that just about every country has approached this in their own way.

Some countries seem to do a standardised education with standardised tests. These tests are then put on a scale and those with grades high enough up the scale get to go on to higher education. This higher education starts with a year of preliminaries in the subject being studied. In this way, anyone with a high enough grade can study whatever they want, and the decision isn’t made until 18 or 19. This seems a far less stressful way of doing things.

On the other hand, some countries look at your grades as you exit primary education, and simply decide on your behalf. When you’re 10 or 11, the state decides what sort of schooling you’ll be given, from academic to vocational, and that’s you. You don’t even get a say in the matter. This too, in its own way, is far less pressurised.

Maybe a mixture of these approaches might work. Teach a broad but shallow curriculum through secondary education, which allows everyone to have a taste of all the subjects. Then run standardised tests. Have these tests look at all aspects of education and learning and then provide school leavers with a range of options based on their individual strengths. The naturally academic would tend towards the the academic courses, and attend higher education.

This may well appear a gross oversimplification, but then the 21st century English National Curriculum remains firmly grounded in the subjects taught to boys at private schools, during the Victorian era. I, for one, think it’s high time for a change!

However, even if such a change does come about, it’ll be too late for my girls. And Ceri, at 15, has found a real liking for the field of architecture. Sadly, her 13 year old self was unaware of this, and didn’t choose the appropriate set of GSCEs.

Which, now, means that Ceri is not in a position to select the ideal A levels to set her up for a degree in architecture. As such, at the age of 16, Ceri is having to run damage control, to boost her appeal to the admission boards of the universities to which she’ll be applying, after her A levels. A levels that she hasn’t even started yet.

Because architecture is a hugely popular course. The entry requirements of places like Bath and Cardiff universities are AAA or A*AA. This is extremely challenging, at the best of times. But even more so when you have to drop your best subject, at A level, in order to pick up one that better suits the architecture entry requirements.

And, because Ceri can’t take the perfect A Levels, she’ll need to focus on the joys that are: Extracurricular Activities, and; Supercurricular Activities. Both of these will be involve additional drains on her time. Time that may well be in short supply, as she embarks on two entirely new A level subjects.

I think that it’s fair to say that most people will understand what is meant by ‘Extracurricular Activities’. These are additional activities that you do outside of your field of study, that show growth and development in you, as a person. They include things like:

- The Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme (DofE)

- National Citizenship Service (NCS)

- Volunteering

- Fund raising

- Sporting achievements

- Musical achievements

Supercurricular Activities, on the hand, are additional activities that you do within your field of study, to demonstrate that you have a real passion for the subject, and a capacity for independent study. This includes things like:

- Enrichment classes

- Supplementary courses

- Reading books and magazines (to add value to personal statements)

- Trips to related institutions and the like

- Entering essay writing competitions

Photo by Sergey Zolkin on Unsplash

Now, I completely accept that all students who are hoping to study a popular course at a quality university will be facing the same issues. It’s just that, because of the decisions she made at the age of 13, Ceri will have to:

- Start two entirely new courses, at A level, and excel at them

- Do a great deal of extracurricular and supercurricular activities, and shine in all of them

And doing both of those things, really well, will still leave her at a disadvantage to those people who have taken the ideal GCSEs and A levels.

Can this really be the best system we, as a country, can come up with.

And, sure, other options are available. Like a foundation year. A year where you fill in all of the gaps in your education, to make yourself the perfect candidate for the course.

But teenagers are no longer paid to go to higher education in England. In fact, that was phased out while I was at university, in the early 1990s, to be replaced by the student loan. Since that time, the cost of undertaking higher education has increased markedly. At the time of writing, each year in higher education will incur two levels of debts:

- Tuition Fees of £9,250

- Maintenance Loans of £4,168 to £8,944 (outside of London)

A bachelor’s degree in architecture (at Bath University) is a four year course. Should you wish to do the follow-on master’s degree, that is another two years. Including a foundation year results in a total of seven years at university.

- Four years at university results in a debt of: £53,672 to £72,776

- Five years at university results in a debt of: £67,090 to £90,970*

- Six years at university results in a debt of: £80,508 to £109,164*

- Seven years at university results in a debt of: £93,926 to £127,358*

* Please be aware that the year of the foundation course and the years of the masters’ course may be charged at different rates.

So, there’s a lot at stake here!

How can a teenager as young as 13 be expected to bear the pressure of making subject choices that lead to decisions about higher education and debts of around £100K?

Photo by Pepi Stojanovski on Unsplash

They can’t.

It’s the height of stupidity!

It’s too late to improve this system to make it easier for Ceri to get on an architecture course. But the thing that astonishes me is that this is exactly the same situation that meant I couldn’t do marine biology and oceanography. And that was literally a generation ago. How can things not have improved in 30 years?!

Will things have changed in 30 years time? Will my teenager grandchildren still be faced with the pressure of making higher education related choices, at 13 or 14?

I certainly hope not, but I can’t do anything about that now.

What I can do, is help Ceri with her extracurricular activities and prevent her having to miss out on her dream job, like I had to.

Which is why Ceri and I will be doing the Tough Mudder on the 18th August. Ceri plans to raise £1,000 for the Somerset Unit for Radiotherapy Equipment (SURE). This is the charity that supports the Beacon Centre, where I received all of my chemotherapy treatments in 2014 to 2016.

To be fair, she’d have done this fund raising anyway, but having it count as an extracurricular activity is just the icing on the cake. Should you wish to make a donation to SURE, please visit Ceri’s Virgin Money Giving page.

The pressure on Ceri, as a teenager, to make the best choices about her higher education have been difficult. They continue to be daunting. But she’s determined to be an Architect. And she’d not going to take no for an answer.