Being told you’ve got bowel cancer is a very difficult thing. And even more difficult to take in. Unfortunately, it’s the beginning of a process, not an end. Before a treatment plan can be worked out, the consultant in charge of your case will need to know everything they can about your cancer. And that means a diagnosis. And getting a diagnosis of bowel cancer isn’t straightforward.

When I was told that I had bowel cancer, I was also told that a CT Scan would be booked for me, and to wait for that call. In the meantime, I had really big decisions to make about with whom I should share my news. And how much to tell them.

For me, breaking bad news about my cancer to my loved ones, is one of the most difficult aspects of the whole thing.

My daughters were 12 and 10, at the time, and we decided to keep them out of it at this stage. All I knew was that I had bowel cancer. I wouldn’t be able to answer the questions they would inevitably ask, until I had a proper diagnosis of bowel cancer. So we decided to wait until we had all the answers before discussing anything with them. This felt dangerously close to lying and I didn’t like it at all. But I couldn’t think of a better solution, so that’s what we did; pretended that nothing was happening.

But I realised that I couldn’t do that with my parents or my brothers. If the situation was reversed, I’d want to know. Which meant I had to tell them. And that meant breaking the same news, three times, in three different conversations, while holding it together myself. To make matters worse, I was still painfully bloated from the colonoscopy.

I won’t go into the details about how these conversations went, I don’t imagine I have to. It sucked!

Having told everyone I intended to, I went home and got on with what came next. The waiting.

The waiting is draining. It is debilitating. Also terrifying. It is a time full of sleeplessness and guilt. It is a time of repetitive, negative thinking and, if you’re not mindful, it can be a time of depression.

To counter some of these effects, I took to writing a journal. That journal forms the basis of these posts.

For anyone in a similar position, I’d suggest trying to fill the void of waiting. Exercise, if you can; let endorphins take some of the strain. Take up a project, something you’ve been wanting to do but putting off: let that fill your time. Share your thoughts, either with someone you love and trust, or with a journal – get it off your chest. Try to do something other than dwell.

For me, my initial wait was just 4 days, at which point I was given the date of my CT Scan, which would be just another 8 days later. A total of 12 days…

12 days doesn’t seem that long a time now. But, re-reading my journal from that time, I was really struggling. But I made it. I wrote more than 6,500 words in those 12 days, mostly trying to second guess the future. None of those guesses, incidentally, was even vaguely close to what actually happened. But I made it to my CT Scan.

CT Scan

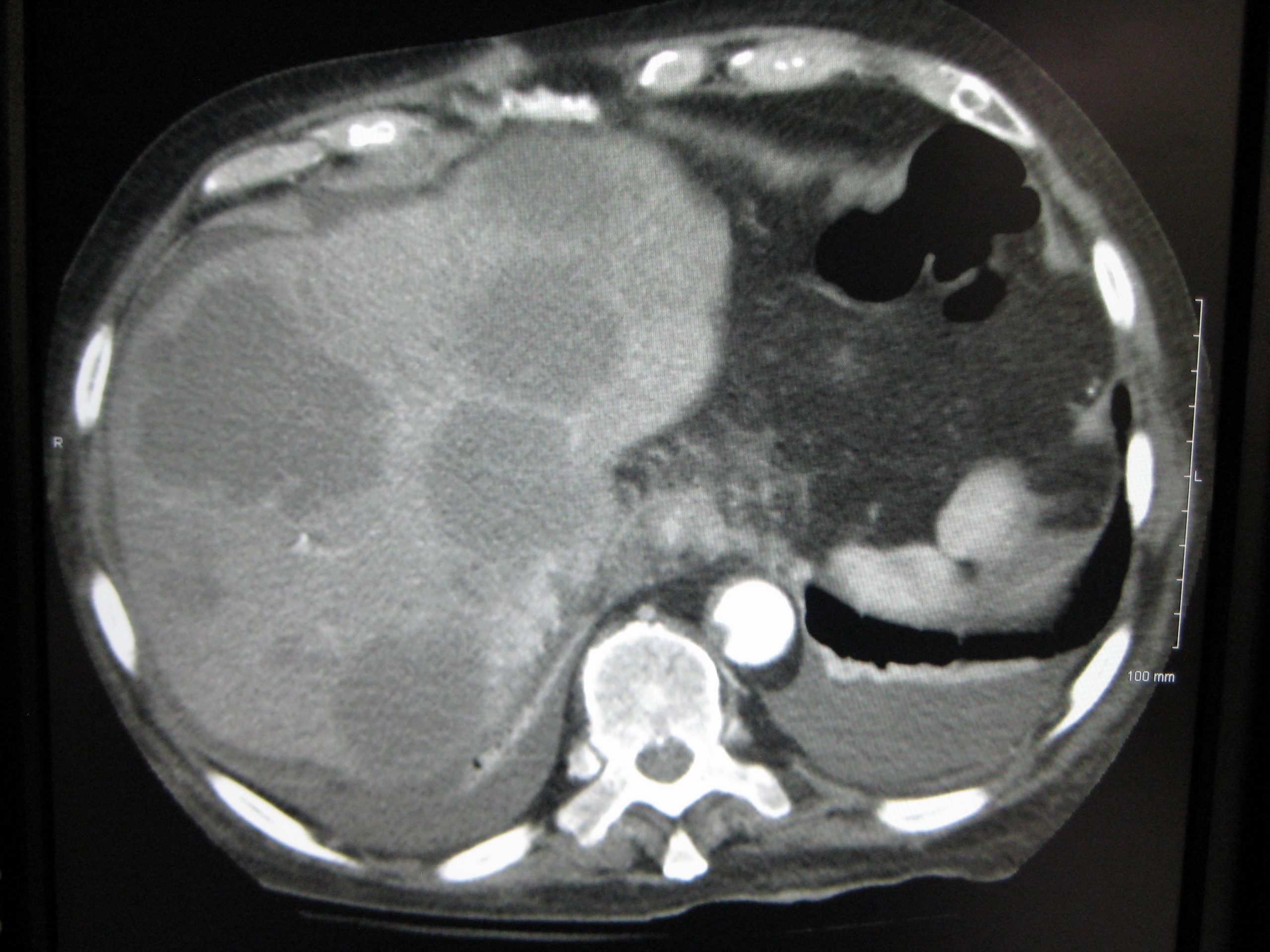

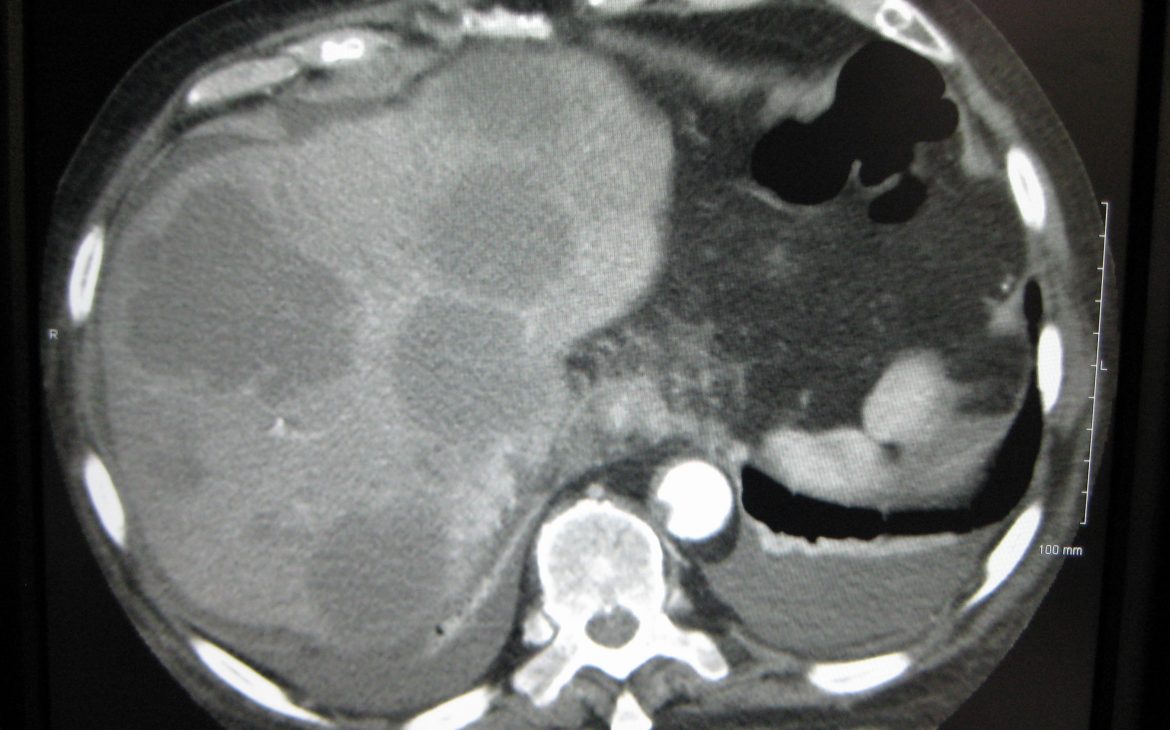

I had to read up on CT Scans, because I didn’t know what they were. It turns out that it’s a focused, directional X-Ray that produces very thin two-dimensional slices, which, when lined up correctly, provide a three-dimensional representation. Pretty cool, really.

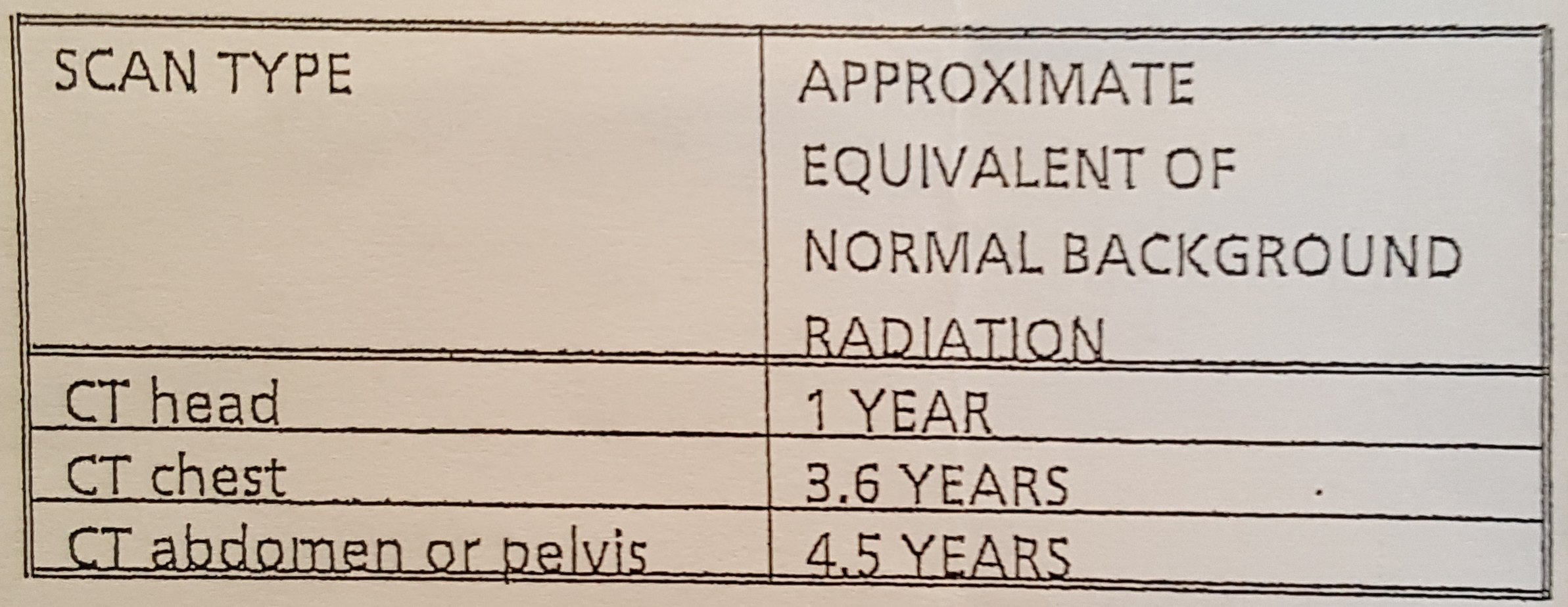

To be fair, the hospital sent me one of their Patient Information sheets, which was very useful and contained details about what the procedure involves. And the type of radiation dose to expect.

A lot has been made about the amount of radiation that is received from a CT Scan and, at first, it can seem quite worrying. During one of my more… unscheduled visits to hospital, which would come much later, I asked one of the doctors about this CT radiation issue. He explained that while CT Scans did emit radiation, there had never been a documented case of this leading to cancer. In any country, and regardless of how many times people were scanned. And that was the last time I worried about the radiation from CT Scans.

The NHS describes the process of a CT Scan like this.

For me, the strangest part of the procedure was arriving at the waiting room and, having been told to fast for the previous 3 hours, I was presented with a big jug of water and told to drink it slowly over the next 40 minutes. You are allowed to use the toilet during this time, which can be useful, because you’re also allowed to drink water during the fasting period.

Another odd experience was, sitting in the, typically, quiet waiting room and hearing a computerised voice in the background. Every now and again, we’d hear something like, ‘Take a deep breath’ or, ‘Breathe normally’. I think there must have been a lot of first timers that day because there were several surprised looks and then laughter.

I was laughing. With strangers. While I was waiting for the scan that would tell me whether I would live or die. It was strangely comforting.

After the drink, I was taken through to a staging area by a nurse. There was the inevitable questionnaire and then the changing into the horrible backless gown. The gown can be avoided, if you’d prefer, by wearing clothes without any metal components. Nowadays, I always go to scans wearing jogging trousers and tee-shirts, and am rarely asked to change into a gown.

From the staging area, you’ll be taken into the scanning room, where you’ll be faced by something like this:

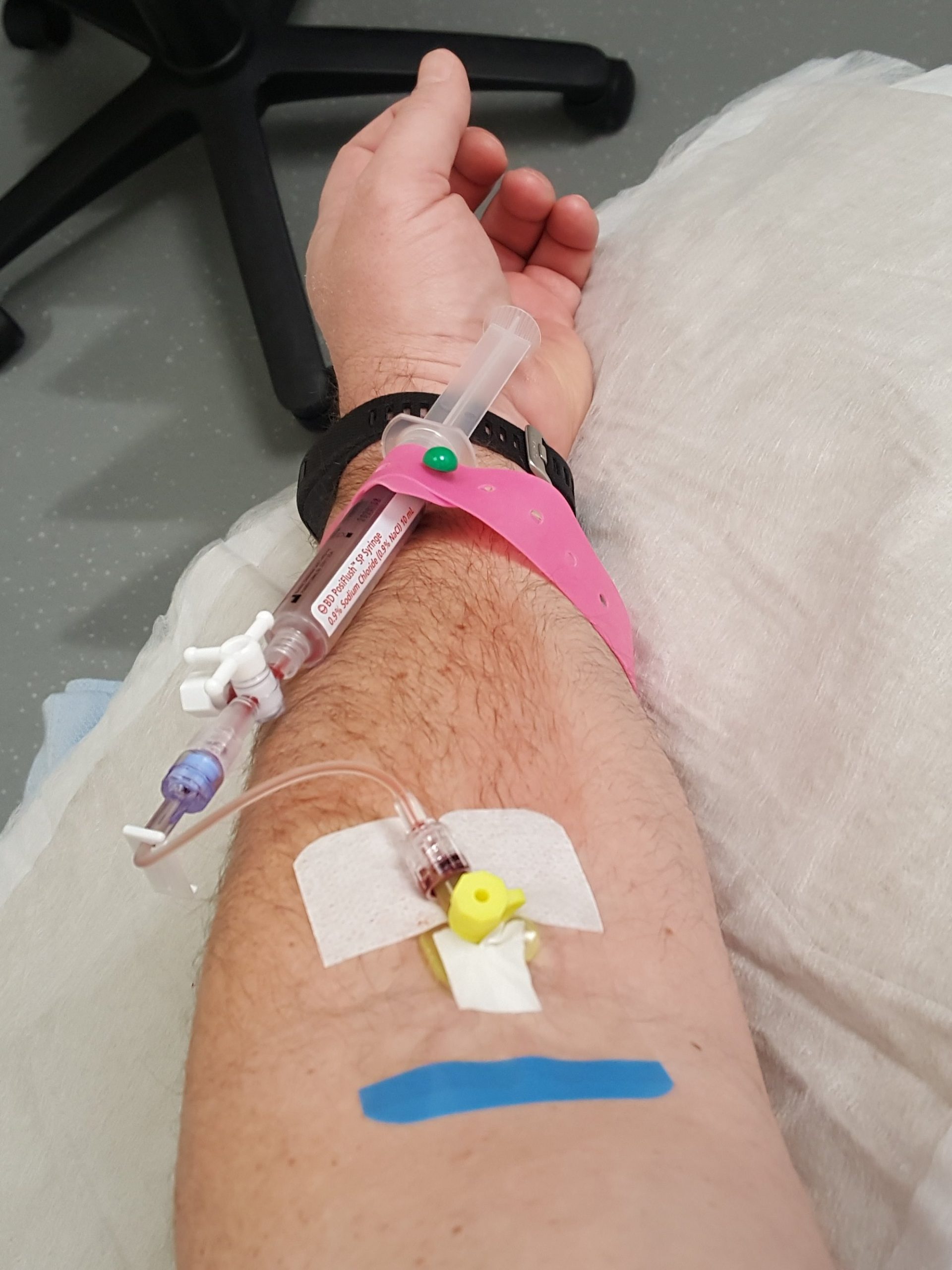

You’ll be arranged on the bed, with feet towards the scanner. You’ll then have a cannula attached to either the back of your hand or the inside of your elbow (apparently this area is called the Cubital Fossa!). The cannula is to deliver an iodine containing contrast medium. Once you’re all set up, the medical staff will disappear into a radiation-proof booth and communicate over a speaker.

The bed moves through the scan while you lie there. The first pass may just be to make sure you’re lined up properly. The next pass will be the first scan. You’ll then be told that the contrast is going in and you’ll hear a pump making this happen. After that, it’s another pass to scan you with the contrast in your system. It’s the difference in the two scans that leads to the diagnosis of bowel cancer.

The contrast has some strange, but very short term, side effects; maybe a minute or two. You’ll feel a hot flush spread over your body. There is likely to be an odd taste in your mouth. And, oddest of all, you’ll feel like you wet yourself. You won’t have. But it’ll feel like it. Very strange! But very quickly gone.

And that’s it. They’ll remove the cannula. Let you to get changed, if you need to, and ask you to wait for 10 minutes, in case there’s a reaction to the contrast. After 10 minutes you can leave, no need to tell anyone; that’s how unlikely a reaction is. But if you are going to have a reaction, the waiting room is the place to be.

And then it’s back to the waiting. For the results. Don’t ask the scanner staff, because they’re not allowed to say anything.

Fortunately, I only had to wait 2 days.

Initial Diagnosis of Bowel Cancer

My first diagnosis of bowel cancer was traumatic.

When Julie and I arrived, there was the surgeon and two colorectal cancer nurse specialists. It didn’t seem likely that being in a meeting where you’re outnumbered by doctors and nurses was a good development. As, indeed, it was not.

So, the surgeon started explaining the findings. The biopsies from the tumour that he’d taken during the colonoscopy were malignant. No surprise there.

He then said that there were shadows on the liver that were likely to be metastases. And that there were six to eight penny-sized tumours studded around both lobes of the liver. There was also, apparently, some activity in the local lymph nodes. The surgeon then paused, because I was no longer looking at him, and he asked whether he was going too fast.

He wasn’t going too fast, it was just that the world was closing in, and I was trapped thinking about how I was going to tell this to Mum and Dad and the girls.

But I needed to hear what he had to say, so forced myself to focus and told him I was considering the probabilities of the five-year survival rates. I don’t want to discuss survival rates here, because a lot of people really don’t want to know. I’ll cover my thoughts on survival rates in a different post.

What I knew, though, or thought I knew, was that 7 tumours on my liver, and metastases (mets) in the lymph nodes, was the end of me. Especially as my bowel was now obstructed by the tumour and I was having to go to the toilet four times a day, with little result. I was prescribed laxatives for this latter issue, which really helped.

Then I was told that I would need chemotherapy (chemo). I was also told that, because of my age and fitness, the surgeon would be willing to operate. And that he’d find a liver surgeon, of an equally aggressive mindset, to take on the liver mets. But that I’d need more scans first, and that an MRI Scan and a PET-CT Scan would be booked in for me.

At this stage, I wondered whether the chemo and surgery route was the best one. I reasoned that, with all that cancer, I couldn’t have more than a year left; did I really want to spend 8 months of it drugged up on chemo and recovering from surgery? That didn’t seem to be the best use of my remaining time with Julie and the girls. So I asked how long I’d survive without treatment.

This was not well received by anyone, particularly Julie. After I explained my reasoning, both the surgeon and the lead colorectal cancer nurse specialist made it clear that their primary concern was always going to be my quality of life. They said that, by going through 9 months of tough treatment, I could be cured. If I refused treatment, I’d almost certainly be dead by Christmas.

That Christmas survival time turned out to be wildly optimistic. I did three months of chemo and my bowel still ruptured in October, between surgeries. Without treatment, I doubt I’d have seen July.

Like I say; a traumatic meeting.

And then I had to explain all this to Mum and Dad. Then to each of my brothers. And then each of my daughters, because one of them was away on a sleepover.

Telling my 12 year old that I had cancer was the worst day of my life. Until the next day, when I told my 10 year old. We didn’t tell them everything. But we had to tell them something because, with everyone in their family upset, they were starting to realise that something was up.

And that meant that the parents of their friends needed to know, to explain why the girls were feeling sad. And the managers at work needed to know, because Julie was going to be taking time off. Word was starting to spread, and not in a way I felt in control of.

So I posted my news on Facebook. Because, if what someone is eating for dinner is newsworthy, then a diagnosis of bowel cancer sure as Hell is. Besides, it made it easier for me; rather than having to tell the whole, sorry tale to everyone, as I met them, I could tell everyone at once. What I didn’t expect was the supportive comments that I received. On more than one occasion since, I’ve had my spirits buoyed by the support I’ve had online.

And so, back to the waiting.

MRI Scan

We were told in the meeting, that I’d have the MRI Scan within two weeks. We both questioned what seemed to be an impossibly long period of time for something so serious. And that’s something that I’ve managed to come to terms with over the last few years; the NHS is a busy thing, there’s always a longer wait than you’d hope for. But, and this is an important but, the wait won’t impact on your chances of survival. Starting chemo today, or two weeks today, makes virtually no difference.

While you’ve just found out that you’ve got cancer, the tumour has been growing for a very long time. It’s hard to accept but two more weeks to your tumour, is no time at all. Which means two more weeks to start your treatment, won’t impact your chances of recovery.

As it was, there was a cancellation, and my time slot was moved up and I only had to wait 5 days. Of course, being me, I analysed this development to within an inch of it’s life. I decided that, in the case of a cancellation, the person who gets the slot must be the one they’re most worried about. Which didn’t do my mindset any good. Then I decided that they wouldn’t give that slot to someone for whom there was no hope, so I must have some chance.

This type of thinking went on a lot during this time… It was exhausting.

The scan itself followed much the same routine as the CT Scan, but the pattern was reversed. In the CT, it’s 45 minutes preliminaries and 15 minutes scan. With the MRI, it’s 15 minutes preliminaries and 45 minutes scan.

The NHS describes the procedure for an MRI Scan here.

The machine is different as well. The bed arrangement is the same but the depth of the machine is greater. I always feel like I’m a torpedo being moved into the launch tube. It’s a tight fit and you’re strapped into place with a chest piece. If you’re claustrophobic, let them know.

This scan also involves an injection, this time of, what was described to me as, ‘rare Earth elements’. Looking it up afterwards, I think it was Gadolinium. Not that it matters what it was, there were no side effects and that’s all I was interested in.

This scan is rather noisy, so you’ll get headphones and a choice of music played down said headphones. There will also be a set of automated commands. Although, there can also be commands from the technicians running the machine.

It’s important to keep your breathing steady and deep during the scan process, because you’ll have to hold your breath quite a few times, and it’s important that you don’t move during the active scan phases. Breathing counts as moving. So don’t let yourself get breathless; keep it steady and deep.

And, once you’re done, you’re done. No need to wait for 10 minutes after the procedure, you’re good to go home.

PET-CT Scan

The PET-CT was only a week after the MRI Scan, which was nice.

I filled most of the intervening time with a trip to London with Julie and the girls. That’s where we got the Cowboy photo shoot done. It was a lovely trip and a wonderful distraction from my woes. I strongly recommend filling your time while you’re waiting for scans and results.

The PET-CT, while a variation on the theme of the other two scans, is a whole new level. The NHS describes it here.

For a start, it has a long preliminary process and a long scan process, and you have to fast. For another thing, the injection you get here really has side effects. The side effects, though, don’t really affect you, so much as the people around you. Basically, it’s assumed that you’re mildly radioactive and you have to avoid young children and pregnant women for 6 hours after the scan. I went for a walk with my parents after this scan. Dumb idea, I was too weak for that. I went to the cinema after the next one, which was much better. You don’t glow in the dark, I checked…

Again, much can be made of the dose of radiation you’ll receive and, again, until there are reports of it actually causing someone harm; I refuse to worry about it.

Take something to read or watch because, after you’re all signed in and you’ve received your dose of radioactive sugar, you’re supposed to sit still for a good 45 minutes. The reason for this is that the sugar will become concentrated at the most active cells. If you stay still, this will be the cancer cells. If you move around too much, it will also be the muscles you’re using to move. Which will confuse the scan.

After you’ve rested and allowed the cancer cells to eat their fill, you’re taken to the toilet and asked to urinate. The scanner staff will be keeping their distance by this stage. Don’t take it personally, they need to keep their cumulative dose down and they’re around a lot of radioactive people.

Then it’s into the scanner room and onto the bed.

I confess, of all the scans, this is the one I find most uncomfortable. The bed is quite narrow and I’m… not. My arms are always arranged over my head. And, while there is an arm support, my shoulders always end up feeling very uncomfortable. Epic pins and needles and then numbness. The ache passes quickly enough after the procedure ends but it’s definitely no fun.

The scanning process is also different. You can just keep breathing and the scan will work around you. After a bit of experimentation, you can work out at what point in your breathing cycle that the scan operates. You can then adjust your breathing accordingly to speed the process up. If memory serves, it’s at the lull at the end of the exhale.

Once the scan is done, it’s just a case of fighting your way off the table, massaging some life back into your shoulders and then finding a way to avoid women and children for the next 6 hours.

Actual Diagnosis of Bowel Cancer

I was now waiting on the hospital to hear a date for the next meeting. This wait was particularly difficult because there was no schedule.

A week after the PET-CT Scan, I got a call from the lead colorectal cancer nurse specialist to, I assumed, book a date for the meeting. But, no, it was my actual diagnosis of bowel cancer.

Rather than make me wait, and because it was good news, the decision was made to tell me over the phone.

And that was the odd thing, the diagnosis of bowel cancer was good news. The scans, you see, revealed that at least 5, of the 7 lesions on my liver were haemangiomas. While still a sort of tumour, haemangiomas are benign and nothing to worry about.

I only had one, or maybe two, tumours in my liver!

And the surgeon had been on the phone to Bristol, where the liver specialists are, and surgery on the liver tumours was an option.

I was thrilled. I had received a diagnosis of bowel cancer with at least one liver metastasis, and I was over the moon. By my estimation, compared with where I was with 7 liver mets, my chances of survival had improved by an order of magnitude.

I asked what would happen next, and was told chemotherapy would happen next. And to wait for a call…

3 thoughts on “Getting a Diagnosis of Bowel Cancer”

Hi Peggy,

I’m sorry to read about your news, and am so sorry for your loss. I’m sorry, also, that it’s taken so long to reply; I was so focused on getting the first part of my story out there, that I never took the time to work out how to reply to comments.

Thank you for your lovely and moving words. It’s been a tricky year for us, with three surgeries, but the latest scan results are clear. So we’re building up to an epic Halloween and then looking forward to a nice, family Christmas and, generally, taking your advice; to spend lots of time together.

I hope that you, too, are managing to stay strong.

All the very best,

Paul.

Hi, just stumbled on your blog this year. From all your narration, I suspect that my late husband died from colon cancer because his symptoms were exactly how you described you felt. Unfortunately the doctors in at national hospital, Abuja Nigeria had no clue to suspect cancer. He was passing out bright coloured lumps of blood for two weeks till he gave up. He was only given palliative medicine till he passed on. Something they could have looked for aggressive solution! How are you now as I can see this blog was last updated by 2018.

Endy from Nigeria

Hi Endy,

I am so sorry for the loss of your husband.

It sounds like he had a much more aggressive version of the cancer than I did.

I’m doing okay, thanks. No cancer issues for the last 4 years.

But other things have kept me away from posting.

I wish you well,

Paul