This post is the third in a trilogy, encompassing some of the conversations I’ve had with my daughters about the current state of sexual politics. The first of the posts looked at Feminism, and the second at Toxic Masculinity. This final aspect of the topic ties everything together, as I discuss Gender Equality with my teenage daughters.

I’m using the term ‘gender equality’ here, because it’s the phrase I used in the post on feminism. In essence, though, I’m really talking about the concept of ‘sexual equality’, because I’m only comparing men and women. I don’t feel best suited to get involved in discussions of the many other available gender options. This is mainly because I can never keep track of how many there are, and I don’t understand the various distinctions properly. This ABC News article, for example, identified 58 gender options for FaceBook users.

The other thing that I’m going to restrict myself to, is talking about countries in the West. I have no experience outside of First World issues and don’t feel in a position to comment.

Wikipedia defines gender equality as follows:

The state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing different behaviors, aspirations and needs equally, regardless of gender.

Which, frankly, all sounds like good stuff.

My daughters seem to think that, on this basis, gender equality has been achieved in our household… By which I think they mean, that I know my place!

20 years ago my wife and I started an asbestos consultancy, G&L Consultancy Ltd. After about 10 years, it was decided that things would operate more smoothly if only one of us was running it. We agreed that Julie would run the company, and I would run the house. And that’s how it’s been. Additionally, both of my daughters will be starting university, over the next couple of years; one to take Pharmacy and the other to take Architecture.

So, of the three women in the household: one owns and operates a company that employs 80 people; one is planning to become a hospital pharmacist, and; one intends to be an architect. I’m not sure what else they could ask for…

I hope they’re right.

The most likely response to this will be: “Equal pay!”

Because, when it comes to issues surrounding gender equality, the gender pay gap gets mentioned a lot. This is certainly the area of gender equality with which my daughters were most familiar; despite never having had a job… Hint! Hint!

The problem is that the ‘Gender Pay Gap’ is actually two concepts with very different meanings. However, a lot of talk about this subject seems to jump between the two concepts, without saying when and why. The two concepts are:

- A gender gap in the median earnings (or lifetime earnings)

- A gender gap in wages for doing the same job, with the same qualifications

The difference between these two, very distinct, concepts is quite well summed up in a BBC report called, firms drag their feet on gender pay gap reporting. In this article, it states:

The gender pay gap is not the same as unequal pay. It doesn’t tell us whether women are being paid less than men for the same work, which has been against the law since the Equal Pay Act was introduced in 1970.

However, the pay gap does give us a measure of the differences in men and women’s working patterns: different occupations, part-time roles being predominantly female – and the lack of women in senior roles.

On the American Association of University Women (AAUW) website, in the article, The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap, there is the following definition:

The gender pay gap is the gap between what men and women are paid. Most commonly, it refers to the median annual pay of all women who work full time and year-round, compared to the pay of a similar cohort of men.

As you can see, this definition does not compare ‘like for like’ work.

And this is where it gets complicated. Largely because two groups form and they just shout at each other. One group will say that, the reason that the median pay for women is less than men is because women are undervalued and oppressed by men. The other group will say that, the median pay for women is less than men because of the career choices made by those women.

Both groups cite studies and reports from various impressive sounding sources. Neither side will listen to the other. There’s just lots and lots of shouting.

It seems to me that the ‘unequal pay’ version of the gender pay gap simply doesn’t exist in the UK. Certainly not at the point of employment. If you’re recruiting a bunch of graduates, and they’ve all got the same grade, they’ll all start on the same salary. I do think, though, that this level playing field tends to become pretty bumpy, pretty quickly. As for the reasons why this happens, that would depend on which group you’re shouting from.

Maybe differences in working practices between the genders? Perhaps an old boy’s network and a glass ceiling? What about both…?!

But I do wonder about the ‘glass ceiling‘!

I was born in 1970, when the Equal Pay Act was introduced in the UK, so I think it’s fair to say I’ve lived through some significant changes. One of these has been the rise of the entrepreneur.

If you look at the Wikipedia list of entrepreneurs of the 21st century, a vastly disproportionate number of them are men. And I don’t understand why! For a while now, more women than men have been going to university. Every year sees more female graduates than male. Why aren’t women taking advantage of this to build their own firms and businesses? Their own futures?

I know it can be done, because Julie’s done it. And she says that she’s never come across a glass ceiling in her life.

There is also never any mention of the ‘glass floor’, for women. There are any number of roles where women are incredibly underrepresented. Jobs that need doing. Jobs that women could do. And, as the definition, above, states: “gender equality includes economic participation.” Yet a lot of a certain category of jobs just seem to be left for the men to do. Economic participation be damned! Jobs like:

- Coal miners

- Oil workers

- Garbage collecters

- Car mechanics

- Roofers

- Fire fighters…

Funnily enough, some of these jobs are really well paid. And, of course, if a woman took on one of these roles, she’d also be paid at the same rate as a man. As well she should. I mentioned this to my daughters and while they agreed that gender equality meant that more women should be doing these jobs, it wasn’t going to be them!

In reality, though, there are instances when men and women are paid at different rates for doing the same work. Modelling, for example, as an article in HuffPost points out:

A 2013 survey by American magazine Forbes estimated that top model Bundchen had earned US$42 million in the previous year, 28 times the amount the best-earning male model, O’Pry, managed to pull in.

I also applied some maths to the 2017 Wimbledon champions…

Source: The Shillong Times

Wimbledon, to much fanfare, pays its male and female winners the same amount of prize money. In 2017, this was £2.2 million. But the winners, Roger Federer and Garbiñe Muguruza did vastly differing amounts of work, to get the same amount of money.

- Muguruza played 133 games across 568 minutes, earning her £3,873.24/minute

- Federer played 196 games across 697 minutes, earning him £3,156.38/minute

- This means that Federer was earning at a rate of 81% of what Muguruza was paid…

Not just a gender pay gap, but actual uneven pay!

There are, of course, arguments in the other direction. The US and Australian women’s football teams are demanding that they be paid the same as their male counterparts, in tournaments like their respective World Cups. They argue that this gender pay gap is also uneven pay.

However, there is an underlying issue at play here; that of revenue.

The men’s World Cup generates so much money that there is plenty to go around all the male players, no matter where their teams finish. The women’s World Cup, however, doesn’t generate anywhere near the same amount. There just isn’t the revenue to draw from, to pay the female players the same as the male players get. In terms of the percentage of the revenue that goes to the players, though, the women actually do better than the men.

But, for me, this doesn’t get to the heart of gender equality in sport.

True gender equality in sport means that men and women should be treated the same, as in other lines of work: as equals. For there to be true gender equality, all footballers, regardless of gender, should attend selection, and the best players get picked for the team. But where would this leave the female players?

To put it into context, both the US and Australian women’s national sides lost to teams of Under 15 boys. This is not to say that either of these matches were played as fierce competitions, they weren’t. Maybe the women’s teams would have won, if they’d played all out. Maybe not. It doesn’t really matter, the point is that the national women’s sides are about the equivalent of the academy sides at club level.

If international standard women footballers are playing at the level of academy boys, they are not playing at the same standard as their male counterparts. In which case, this is not an example of uneven pay…

The reality, though, is that in sport, much like TV, film and modelling, the market revenue dictates the amounts paid. Some people simply have more earning power. Be it a female model, or a male footballer; there are market forces at play that cannot be ignored.

There is, however, much more to gender equality than the pay gap.

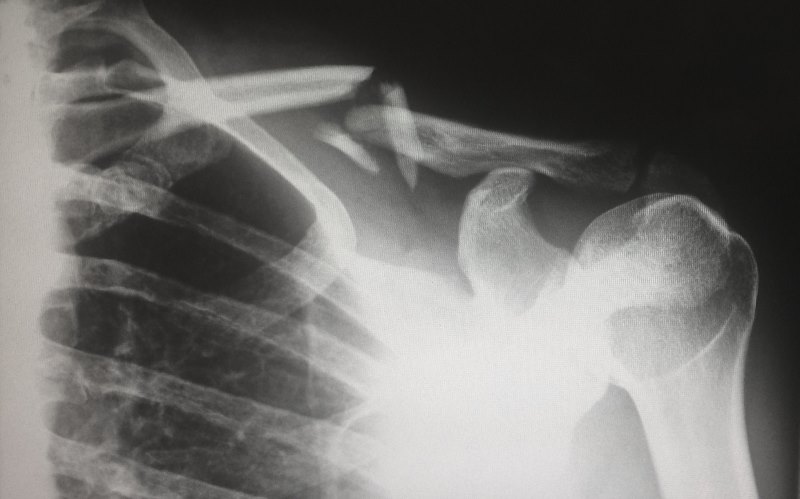

Even within the field of employment, there is more going on. For example, the rate of reported non-fatal injuries per 100,000 employees, from 2013 to 2018 in Great Britain was:

- Male – 335

- Female – 189

Which means, according the the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) figures, men are 1.8 times more likely to have a non-fatal injury at work.

Photo by Harlie Raethel on Unsplash

It’s when you look at the fatalities that things are brought into sharp focus. The rate of fatal injuries per 100,000 workers from 2013 to 2018 in Great Britain was:

- Male – 0.81

- Female – 0.04

So, based on the HSE figures, men are 20 times more likely to be killed at work…

And, yes, there are reasons for this. Things like:

- The job choices that men make

- Male working practices and habits

- The lack of women in dangerous roles

All the same things talked about with the gender pay gap, only in the other direction. Funny how that works out.

The thing is that these accident and injury rates clearly indicate a lack of gender equality. Surely men and women should be sharing the most dangerous jobs equally…?

But work isn’t the only health related example of an imbalance between the genders:

- More boys than girls are born, at a ratio of 105 males for every 100 girls

- Males account for 75% of suicides in the UK

- In the UK, life expectancy, at birth, for 2017 was:

- Males – 79.2 years

- Females – 82.9 years

So, while more boys are born, they can expect to live, on average, 3.7 years less than the girls.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), a lot of this is simply biological in nature. And this is important to note, because there are moves, on some parts, to insist that gender differences are a social construct. Some even go as far as to suggest that biological sex is a social construct. Yet nature disagrees.

And I realise that, for the most part, birth rates and life expectancy aren’t really a part of the gender equality issue. Well, apart from the work and suicide related factors, mentioned above. I only really include it to emphasise that there are genuine biological differences between the sexes, beyond our appearances. And this needs to be acknowledged and accounted for, when talking about gender equality. In the face of all this, to insist that men and women think and act exactly the same way seems disingenuous.

To my mind, it seems obvious that men and women behave differently in different circumstances.

And this can become a problem when men and women are trying to coexist in an area that has been built around the expectations of just one of those genders. The workplace, for example, was a traditionally male domain and was structured accordingly. When women started moving into traditionally male professions, it went without saying that women would have to fit in with the way the men did it.

In some instances, this went on for a staggeringly long period of time before someone looked around and said, “Hang on a minute…!” My daughters were amazed when we talked about the historical aspects of gender equality. Neither of them is much into history. Maybe, if someone came up with turning history into an Xbox game…

At which point, whole professions and industries had to be significantly altered to take into account that there were actually two genders involved now. In a number of cases, this remains a work in progress.

And this is also true for social norms; for decisions about what is right and wrong in society. For a long time, certainly in the UK, the domain of social norms has been female driven. Stemming, really, from one female in particular: Queen Victoria.

The Wikipedia page on Victorian Morality quotes Harold Perkin, who writes:

Between 1780 and 1850 the English ceased to be one of the most aggressive, brutal, rowdy, outspoken, riotous, cruel and bloodthirsty nations in the world and became one of the most inhibited, polite, orderly, tender-minded, prudish and hypocritical.

Or, put more simply, English societal norms stopped being a male domain and became a female domain. Don’t misunderstand me here, I’m not saying that this is a bad thing, far from it. Some of the things that this shift in attitude got rid of were:

- Slavery

- About 200 capital offences

- Child labour

- Animal cruelty (bull-baiting and cock-fighting, at least)

I’m very glad it happened. Indeed, this societal upheaval also introduced, or reinforced, concepts of:

- Evangelicalism

- Charity

- industrial work ethic

- Personal improvement

- Family and duty

- Sexual propriety and restraint

Again, for the most part, all good things.

In moderation!

However, and somewhat ironically, there wasn’t much in the way of moderation to be found. Victorian morals regarding family and duty, clearly established that it was a man’s duty to work and provide. And that a woman’s place was in the home.

I think that we can all agree that we’re right to have moved beyond this particular mindset.

But what we haven’t moved beyond are some elements of the Victorian attitude towards sexuality. Certainly not as it puritans to men.

In the case of women, there has been some progress. No longer is it believed that women are not much interested in sex, and should simply, ‘Lie back and think of England‘,

However, there has been less movement on the idea that men are completely controlled by their sexual urges. Some examples of this are:

- Male medical practitioners need to offer female chaperones when seeing female patients, but not visa versa

- Male teachers should not discipline a lone female student, but not visa versa

- Men who are sports coaches should not train junior female teams without a female adult present, but not visa versa

Photo by Adrià Crehuet Cano on Unsplash

This was another area relating to gender equality on which my daughters had quite a lot to say. They referred back to their school, where a change in uniform policy meant that, if girls wore trousers, they couldn’t have back pockets. If girls wore skirts, the hems had to fall to the knee. Male teachers were told that, despite this being a policy that was intended to be enforced, they could not comment if there were back pockets on a girl’s trousers. Or if the skirt hem was too short… Because it meant that they’d been looking at the backsides and legs of the girls.

And for men, any time you look at the backside or legs of a female, of any age; there must be sexual connotations, right?! Because everyone knows that men are completely controlled by their sexual urges, right?!

No!

Of course not!

Do you have any idea how sodding insulting this belief is?!

How can there be any pretense of gender equality when it’s assumed that the best way to treat male teachers is to assume they’re paedophiles? And, of course, all the pupils know these rules. What precedent do you think this has set my daughters in terms of gender equality. All the pupils at this school, and so many others, are being taught that it’s right to assume that men can’t be trusted around girls.

And the defenders of such policies will then bring up pornography. Because if men like pornography so much, it shows that they’re always thinking about sex. Which is why we have to have these rules in place…

To which, i will respond with one of the bullet points of what defines Toxic Masculinity, from the Geek Feminism site:

- “The expectation that Real Men are keenly interested in sex, want to have sex, and are ready to have sex most if not all times.“

That’s right, anyone espousing such a dated belief is guilty of toxic masculinity…

But, yes, men like pornography, and pornography remains largely frowned upon by society, And this is despite the fact that the vast majority of said society consumes pornography to some extent.

The main difference here is that males typically consume pornography visually. Females, however, tend to consume pornography via the written word. As such, things like the Black Lace ‘erotic fiction’ books are considered to be literature instead of pornography. I’ve seen a couple of those books and they’re the most pornographic things I’ve ever read! And, in terms of genre, romance/erotica sells more books than any other. Women like reading pornography. Men like watching it.

So, given that we all like pornography, if women aren’t thinking about sex all the time, why is there the assumption that men are?

And as the definition of gender equality states, above, we should be: “valuing different behaviors, aspirations and needs equally, regardless of gender.” Which surely means that we shouldn’t be judging each other on the way we consume our pornography. Or, for that matter certain other things.

Take sexual objectification, something for which men are endlessly criticised. I’d just like to point out that between a third and a half of women admit to having a sex toy. How said sex toys can be thought of as anything other then the ultimate objectification of men, is beyond me…

By JVRKPRASAD – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67744202

I simply accept that both genders display elements of sexual objectification, and move on.

And while this last point is largely trivial, there are far more serious consequences from this societal attitude towards sexuality:

- Women receive much lighter sentences than men for equivalent sex offences

- If a drunken couple wakes up after a night of sex, of which neither of them remembers anything, only the man is going to face charges of sex offences

- And only the man will find his name in the news

- The wording of UK law means that it is impossible for a woman to rape a man

None of these things speak of gender equality

Maybe these are just examples of ambivalent sexism. Because that is a two-way street. It isn’t just things like:

- Holding the door open for women

- Giving up your seat on public transport for women

- Saving the ‘women and children’ first in hostage or emergency situations

So, while I get that ambivalent sexism is annoying to women. And I understand that the residual Victorian attitude, of men looking out for women can seem condescending. I would suggest that the assumption that men don’t make good parents is worse.

Please don’t think that I’m trying to paint a picture in which there are no gender equality issues from the female perspective. I’m not, because of course there are.

All I’m trying to do, here, is capture the essence of the conversations I’ve had with my daughters on gender equality. From their perspective, they feel they have gender equality. They actually felt that things are moving past equality to the point that the pendulum has swung too far.

Personally, I don’t know about that. There is currently a lot of noise and bluster about progressivism, and social reform, often under the banner of social justice. But the latter has become something of a dog whistle, as applied to Social Justice Warriors. And such terms are seldom useful and do little to advance the discourse. Any more than the constant use of Mansplaining does, whenever a man ventures an opinion.

The reality is that there are people trying to settle scores here. On both sides. None of which helps my daughters in their lives or gender equality. It just entrenches positions and leads to people dragging their heels.

My daughters’ final thoughts on the matter was; that gender equality should be considered from both the male and female perspective, to move it forward in a manner that benefits both sexes.

There’s no point considering social norms solely from the female perspective, any more than there is considering workplace norms solely from the male perspective. All aspects of gender equality have to be considered from the perspective of both genders. Only then will gender equality stop being treated like a seesaw, where one gender falls as the other gender rises. Instead, gender equality can be treated as an elevator, where everyone, including my daughters, go up together.